Robbie

Tenerowicz

Nobody knows Driveline quite like Robbie Tenerowicz. His best guess is that he’s spent something like 10,000 hours training at the facility–though he’s quick to point out that that’s not a claim that he’s mastered anything.

Tenerowicz, or “Byrd” as he’s known here, was Driveline’s first professional hitting trainee back in 2019. He’s seen it all, been through it all. Byrd showed up when Driveline had one hitting cage, on the heels of a bad minor league season in the Rays organization (his words) because of a nagging injury (not an excuse, he says), because two of his college teammates at Cal – Max Dutto and John Soteropulos – were wanting to get their hands on his swing.

“I had a bad 2019 and blamed an injury,” Tenerowicz said. “I was a little hurt, but not enough to be a reason for the bad stats. Dutto had been trying to get me [to Driveline] for a while. That was the main reason to come up. The trust came from having two of my best friends up here, and handing Dutto the keys to the car–the car being my swing.”

Byrd basically received the Men in Black treatment: look at the neuralyzer and let it wipe away what he knew about his swing.

That’s a tough thing to do, but Byrd says it was necessary.

“The first fix was getting rid of all the knowledge about my swing that I thought I had,” he said. “Basically getting rid of all the memories, all the lessons from anybody ever and just starting fresh. I was coming in with a fresh slate, like someone not from this planet who had never heard of baseball before.”

Byrd’s bat speed was slow (he averaged 71 mph in his first assessment), his bat path was too flat (his average attack angle was 4.0 degrees), and his posture was too up-and-down.

So they got to work, with the limited amount of tools and knowledge available to them at the time. Back in 2019 there were no case studies, no biomechanics, no Blast sensors, and no TRAQ.

But they had a template for what they wanted to do, and Byrd’s buy-in was 100 percent. Whatever Dutto and Soteropulos thought was necessary, Byrd was in.

“It’s very important to maximize your playing window of three to four years to try to reach your highest percentile outcomes,” Soteropulos said. “Guys talk a lot about doing that. But when it comes to Byrd, if you look at his actions from 2019 until today, he’s actually done that.”

“Once [Byrd] got into the Driveline ecosystem in 2019, he just never stopped trying to improve,” Soteropulos said. “He is basically the model for what data-driven training can look like…This is a dude who gets as close to his genetic ceiling as possible and has continued to get better by using his resources.”

Even when resources were short, Byrd was working. During the COVID break in 2020 when he was out of organized baseball for the summer, he flew back to Seattle to train with Driveline. Except there wasn’t really a Driveline to train at. The facility, like the rest of the world, was closed.

So Byrd and Soteropulos took a tour of every high school in the Seattle area looking for outdoor batting cages, jumping fences to hit buckets of balls for hours. Security would come for them at one high school, they would load up, and drive to the next one. It was like that from March until July, when the Driveline facility opened back up.

“We’d go anywhere from Bellevue all the way down to Federal Way,” Byrd said, mapping out the 25-30-mile radius of cages. “Some of the schools, the fences were too high. They would have like a 10-foot fence. So we would get to the school and be like, ‘Ahh too high, onto the next school.’ Whatever it took.”

The hard work paid off. The Reds signed him to a minor league contract for the 2021 season, in which he registered a 128 wRC+ over 93 games at Double-A Chattanooga.

2022 didn’t quite look the same, however, and after being granted a release from the organization in early July, Byrd again came back to Driveline to train.

He didn’t take a month off or even a week. No soul-searching. No pondering whether or not it was the end. Byrd played his last game on a Monday, flew to Seattle on Tuesday, and was at Driveline training on Wednesday.

Soteropulos had a new plan waiting for him when he got there.

“When he came back this past season,” he explained, “I was like, ‘Your skill of hitting, we’ve trained that more than anybody else in the entire world, nobody knows more about their biomechanics. Nobody gets more out of their genetics and their frame in terms of generating energy as you do, but your weight room numbers are bad.”

So Byrd started lifting six days per week. His bench press went up more than 40 pounds, deadlift up 60, squat up 50, clean and jerk up 75 – you get the point. In turn, his average bat speed on any given day is now between 74-77 mph, and he’s hitting balls harder than he ever has.

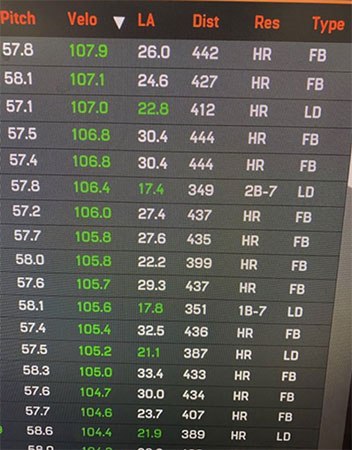

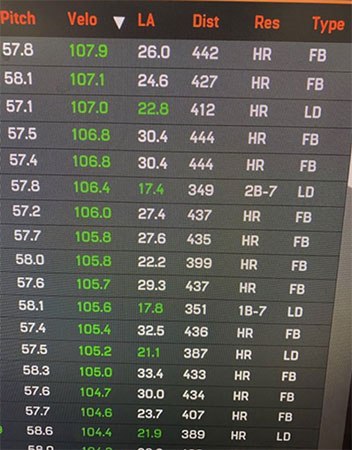

It paid off in the form of a new opportunity for him: he signed a minor league deal with the Seattle Mariners for the 2023 season to take his next shot at the big leagues. Of course, he’s spent this offseason at Driveline ramping up for Spring Training, making 105 mph EVs look routine.

10,000 hours in, Byrd has a whole lot of good baseball ahead of him.