There Are No Golden Rules

Everybody wants a golden rule — a north star to guide them, a one-step solution to every problem, and I don’t blame them. But the unfortunate truth of acquiring and developing any skill, or solving any problem — whether in sports, business, school, or life — is that it’s rarely so simple. Complex problems by their very nature don’t yield to simplicity. They demand nuance, they demand context, and they require deliberate effort. To answer a complex problem with a simple solution is tantamount to miscalculating that problem’s complexity.

Knowing this to be the case, why do we then still chase simplicity and truisms?

The answer is partially embedded in our biology — simplicity feels efficient, and we’re designed to seek it. Evolution has geared us towards seeking efficiency because efficiency once meant survival. Today, however, that wiring leads us astray, causing us to simplify problems that require deeper consideration and stronger solutions. The innate tension between complexity and simplicity is the heart of the issue, and it’s a theme I first heard framed by Anthony Brady on the Driveline R&D Podcast.

Brady explained: “The baseball community loves, and is constantly searching for, truisms within the game and within development.”

Brady’s sentiment echoes that innate tension — we want simple answers as to how we can be the best, but improvement is much more complex than that.

In this context, we can take “truism” to mean “a blanket truth” — an oversimplified statement that seeks universality and aims to solve a problem without accounting for its inherent complexity. While truisms may feel insightful, and while they may appear to be universally applicable, they fail to produce meaningful outcomes. Instead, they offer false confidence and security by reducing the nuance of our most important challenges into inappropriately simple answers.

Player development is not, and never will be, solved via a single variable — it is a matter of systematic and sequential problem-solving. That framework isn’t just true in baseball; it applies to any competitive venture. Yet, so many people continue to ask the wrong questions. Take an all-too-common inquiry, for example: “What’s the missing piece?” On the surface, this sounds like a productive question, but it ultimately reduces the problem to its simplest form, assuming a single, isolated solution. This approach, and question, ignore the complexity of real-world problems.

The better version of that question would be: “What are the missing pieces, and what foundational steps do I need to take to actually address them?” This version acknowledges that gaps rarely exist in isolation and that solving for one variable often requires the building and reinforcing of supporting structures. It reaches beyond surface-level thinking to account for dependencies and context — both of which are key elements in the solving of multivariate problems.

If a problem seems solvable in a single step, it’s a sign you likely don’t understand it well enough to solve that problem. The truly impactful problems — the ones that change industries, careers, and lives — don’t yield to the quick fixes, and they don’t adhere to any supposed truisms. Much the same, by the time a problem is simple enough to be solved in a single step, that problem is inherently not very interesting. The foundational questions have already been answered, and there isn’t much value to be added anymore. The heavy lifting has already been done by someone who has had a much earlier, much more impactful realization than any of us would have to offer.

In contrast, the most interesting and impactful problems are unsolved for a reason. These problems are inherently multivariate and require careful deliberation. Addressing these problems isn’t just a matter of finding the correct answer; it’s a matter of identifying the true signal among the noise and systematically accounting for the complex inter-variable relationships that underlie these problems. This is where truisms fail so miserably — because they attempt to offer blanket solutions to problems that demand individualized approaches.

Consider a more specific example within the context of player development at Driveline: teaching someone to throw an effective sweeper or working to refine their command are both problems that have been sufficiently solved countless times before and will be solved countless times again on an individual basis — they aren’t inherently groundbreaking problems. But even these are complex in and of themselves and thus require specific, non-universal solutions. They require multi-step processes that account for context, key dependencies, and the unique needs of each individual athlete.

Consider these examples even further, teaching an athlete an effective sweeper consists of many variables — finger placement, grip pressure and distribution, arm slot, mechanical variation; the list is seemingly infinite. Refining command can be conceptualized much the same, and it is perhaps even more complex and difficult to improve. Point being: even the problems we look to solve on a daily basis require multi-step solutions and complex considerations — they’re problems worth our solving, so they are also innately multivariate. So too, these are the exact types of problems that truisms fail so miserably to address.

This type of multi-step, all-encompassing thinking is the type of approach that Driveline aims to aggressively employ in our development of athletes — this is perhaps best exemplified by the Pitching Hierarchy of Needs.

Though my opposition to them is hopefully more than clear by now, I’d be remiss to act as though I don’t understand the appeal of a truism — it’s obvious. If I were to offer you a five-step solution to a problem, and the guy standing next to me says he can solve the same problem in one step, I would be ignorant to think that the former holds a flame to the allure of the latter. Humans are coded to pursue efficiency, just as they are to seek paths of least resistance. The issue, however, is that the attractive single-step fix almost never works because, as I’ve said many times now, complex problems demand equally complex solutions. Truisms, in this context, fail not only because they simplify that which is not simple, but because in doing so they do not produce favorable outcomes.

Broadly speaking, favorable outcomes are the base-level unit of analysis for whether a solution is any good. So even if your solution looks good, sounds good, and perhaps even if it is well-received — none of that matters, quite frankly, if the outcome is not favorable. In this way, problem solving is somewhat of a zero-sum game.

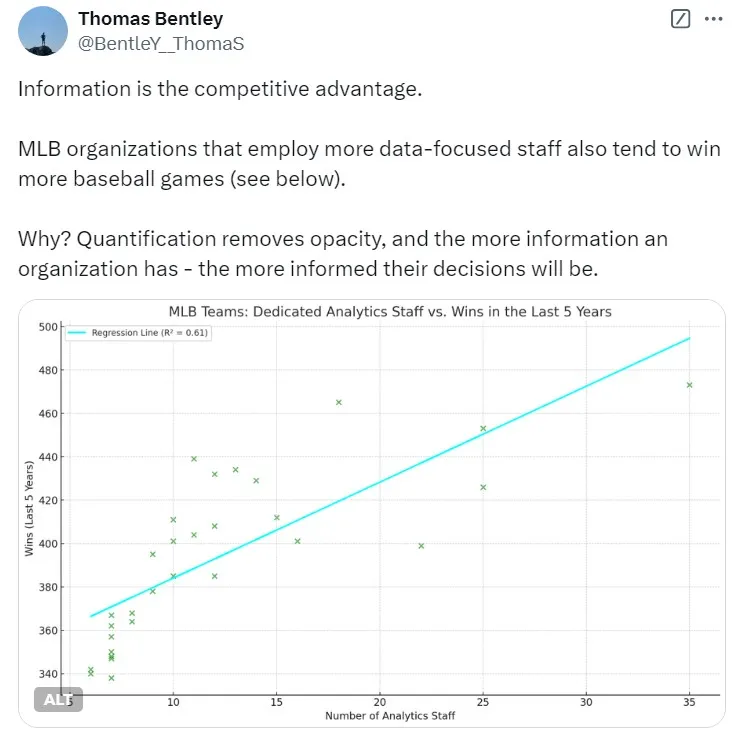

In any competitive effort, we should then understand that a truism — in application — is a competitive disadvantage (we obviously should aim to avoid those). I still believe that information will always be the competitive advantage in any effort — whether that’s teaching a slider, growing a business, or building rockets; the people that are winning are the ones that know more than their competition.

Truisms are broad, unspecific, and veil their inapplicability with a false sense of universality. Information, by contrast, is specific, nuanced, and contextually aware — information is truth and vice versa.

To solve worthwhile problems, we have to reject the simplicity that truisms offer and embrace the complexity that meaningful solutions demand. The hardest problems are the ones with the greatest potential to create value — but they also demand the most of us. Operating on the edge and at fringes — where innovation exists and complexity is commonplace — is indeed difficult, but extremely necessary.

To quote the late Kurt Vonnegut: “I want to stand as close to the edge as I can without going over. Out on the edge, you see all kinds of things you can’t see from the center.”

The center is safe, predictable, and full of people who mistake truisms for truth — there’s almost nothing of impact to be found here because the edge is where meaningful progress happens.

So if our aim is to impact industries, solve the problems worth solving, and create substantial value, we need to approach our problems with the information and complexity that they demand — this is exactly what we aim to do at Driveline.

It would have been extraordinarily easy to chart balls and strikes and call that command, but we wanted to do more so we invented the Intended Zones Tracker.

It would have been inexpensive for us to just put throwing programs in Google Sheets, but we wanted to be better so our software and product teams created TRAQ.

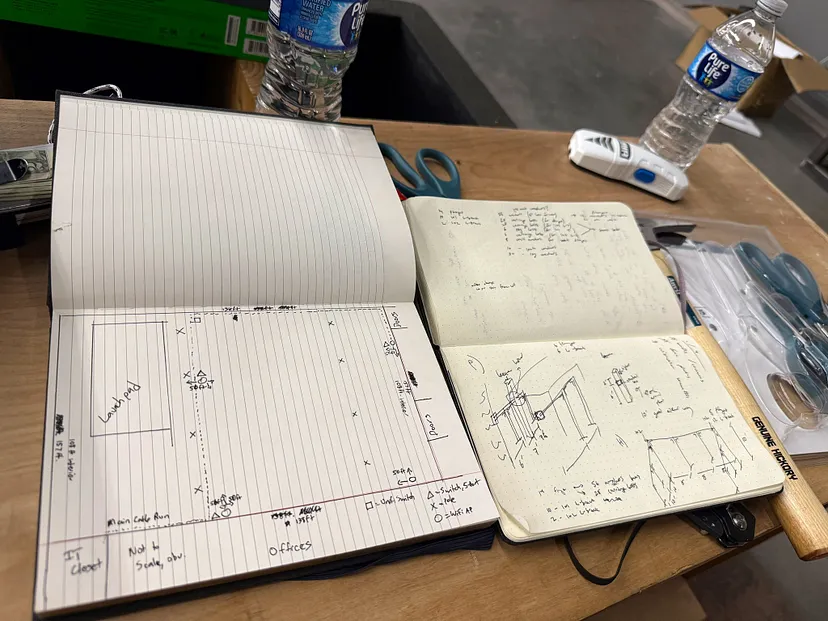

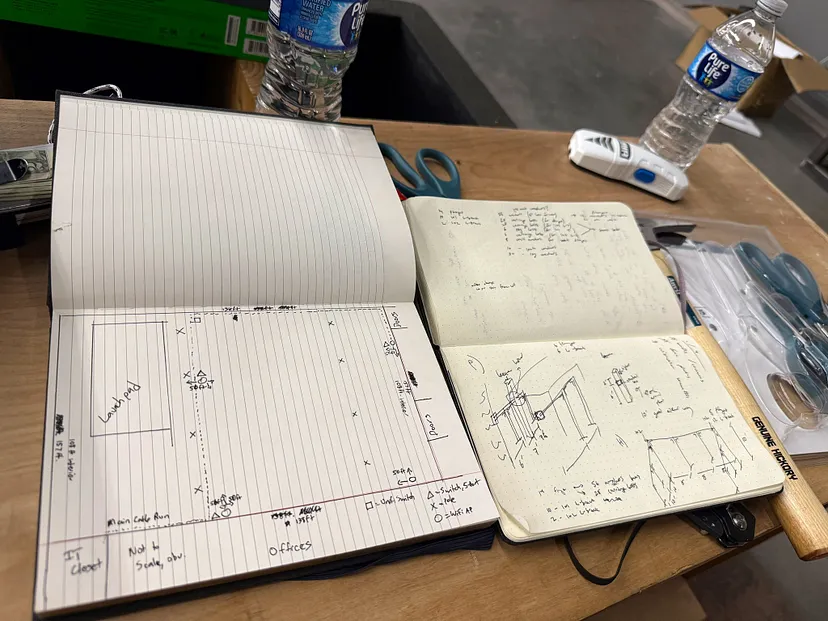

It would have been much quicker to assume that certain mechanical fixes were effective, but we wanted better answers so we improved and proliferated the development of our Launch Pad biomechanical labs.

And it would have been easy to abide by the status quo, but we understood that progress is made out on the fringes. We figured that we ought to look over the edge more often than not if we’re going to do anything meaningful because it was clear that favorable outcomes would follow those who did.

Comment section