Trusting The Numbers: An Exploration Into Data Skepticism

The world as we know it is inherently data-driven; from the very computer on which this thing you are reading is being written, to the complexities of the stock market — modern life, for better or worse, seems not to be much more than the product of a cleverly constructed series of ones and zeroes. In the same vein, and as the proliferation of technological development accelerates full-steam ahead into an era of late-stage industrialization, our ability to capture, quantify, and understand real-world phenomena will only continue to improve and extend its bounds. Such a continuation is not limited only to the worlds of technology and business however, as sports analytics are — despite the observed contention and hesitation that surrounds them — riding the same progressive curve. This aforementioned contention and hesitation are, regardless of any proven efficacy, uphill ideological and philosophical battles being engaged with everyday.

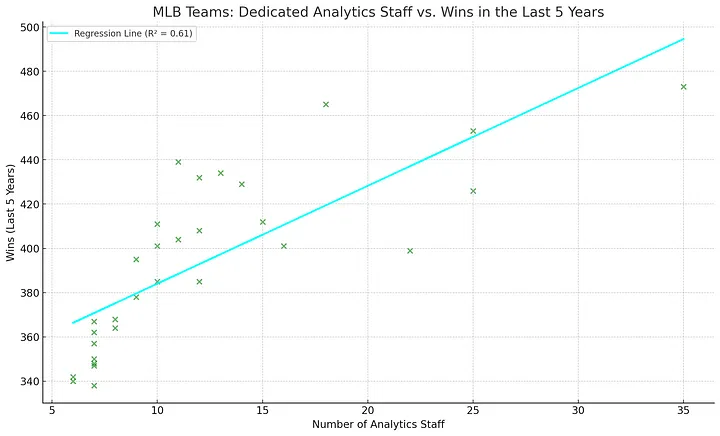

MLB organization quantity of dedicated analytics staff compared to the number of games won by that team in the last 5 season (r² = 0.61).

Asking questions and entertaining skepticism are innately human traits, and while there are biological arguments as to why both may have had and still maintain a socio-evolutionary utility in preserving both our ideas and our person, denying the proven results of these data-driven approaches and the long-spanning success of quantitative reasoning begs the question: in the year 2024, why do we still distrust the data?

A well-founded place to begin answering the question of data skepticism is seen in, of all things, the 2015 film, The Big Short. The film is a somewhat-fictionalized retelling of the intricacies of the 2008 financial crisis, and is — in its own right — very much a story of distrust and skepticism. In short, the film breaks down the means by which investors were able to foresee and capitalize on a housing market crash that only they predicted and understood the magnitude of. At the closing of the story, as the film’s main character — Dr. Michael J. Burry — closes his hedge fund (Scion Capital) in the wake of an unimaginable net gain, a monologue on the nature of selective authority is shared. He states:

“People want an authority to tell them how to value things, but they choose this authority not based on facts or results — they choose it because it seems authoritative and familiar.”

Much the same, the very ignorance to data we discuss is rooted not in fact or authority, but in that we do not understand it, in that we — therefore — do not trust it, and in that we — subsequently — are unwilling to recognize its validity. Humans are subject to cognitive bias and misdirection because we are designed to seek out and follow the path of least resistance. We therein are designed to trust the thing that is, naturally, most authoritative and familiar. Ultimately, the issue of data skepticism is not rooted in convincing distrusting populations that our data is truthful or that our insights are correct, but in understanding why they trust the people, the sources, and the ideas that they trust. Yes, the doubters do need convincing, but even more so — they need to be understood.

Developing an understanding of why we believe the things we do and why we trust who we trust is an investigation into perception and, therefore, is an interdisciplinary undertaking; humans are, by our very nature, complex and multifaceted. Moreover, our perceptions of the world — the intricate foundation of the very question being asked — are informed by an uncountable number of sources including our interactions with other people, our interactions with technology, and our intrapersonal interactions. It is because of this that our derived interpretation and subsequent understanding of our surroundings is largely what determines our relationship with the world — we are ultimately the products of our individual subjectivity.

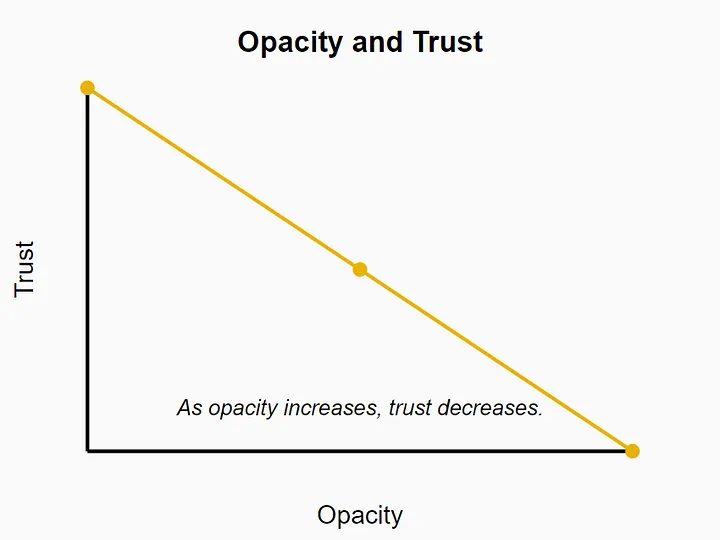

From a technical perspective, the question of data distrust is rooted in the underlying issue of, what we will call, opacity — defined by Jenna Burrell as the degree to which an individual does not understand the thing they are interacting with. Opacity inherently creates barriers to understanding, thereby causing hesitation to accept the result of that process and ultimately distrust towards those responsible for producing the result.

Simply put, “opacity can create a barrier to trust. If people cannot understand how a decision was made, they are less likely to trust it…” (Burrell, J. 2016). This phenomenon is not exclusive to abstract technical concepts, however, as a failure to clearly outline the processes by which one reaches their conclusions would naturally result in distrust towards those subsequent findings in any field — sports analytics included.

While Burrell’s opacity is indeed a prominent issue to be considered in our approach, it is not the only issue — the failure to deliver data-driven ideas to non-data-driven minds is, as Donald Norman cites, a design issue as well. In Norman’s 2013 book, The Design of Everyday Things, he makes the supporting point that user error is, in actuality, just another sub-sect of design error, stating that “Good design requires everything be visible, that the operations be clear, and that there be a good conceptual model which guides the user as to what is possible and how to achieve it.” To Norman’s point, user error is not isolated — rather, it is the result of poor design which ultimately facilitates an erroneous user experience. Much the same, a poorly-designed explanation of data-pertaining concepts to the general populace underlies the populace’s very failure to understand those concepts; their lack of comprehension and willingness to accept something they do not understand is, thereby, ultimately not a failure on their own behalf, but a failure on behalf of those responsible for presenting the information — it is a failure on behalf of data analysts like me, and including me!

Norman further explains that “Well-designed objects are easy to interpret and understand. They contain visible clues to their operation.” From this, we should deduce that if an athlete, a user, or any general member of the greater populace is expected to understand the results of our analysis, it must be presented in a way that facilitates their understanding and mitigates the probability of confusion. What does this look like in practice?

In the same regard that a user’s experience with a piece of technology determines their perception of that device, the experience that an athlete, or any audience otherwise, has with quantitative insights is ultimately determinant in their trust and the perceived validity of that information. By that same comparison, we can then conclude that the job of the quantitative analyst is not only to analyze, but to sell and to present that analysis — and to do so in such a manner that facilitates the audience’s understanding, acceptance, and — most critically — trust in the numbers.

The issue of quantitative skepticism is not solely one of opacity, nor is it one solely of erroneous design; this is, rather, an issue of interdisciplinary consideration. The sociological lens, in its plentiful contrast to that of the technical, offers an explanation rooted in the intricate means by which humans interact with one another. Such a perspective posits that the populace’s hesitation towards and distrust of data-driven methodologies is rooted in perceived power dynamics, social hierarchies, and disconnections in communication.

Power and knowledge directly imply one another, and as author Michael Foucault explains in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of The Prison, “there is no power relation without the correlation constituent to a field of knowledge.” To Foucault’s point, one’s knowledge of a field establishes the perceived power that the individual has within that discipline; moreover, if a quantitative analyst perceives themself and is perceived by others as being highly knowledgeable in their field, they are likely to experience a feeling of power in that field. Because of this perceived position of power, they then place themself and are also placed by others higher on the social hierarchy, thereby perceivably disconnecting themself from the very audience to which they wish to communicate their ideas in the first place. Subsequently, that same audience also becomes distrusting of this individual because they too feel disconnected, and in an effort to share an idea about the world, we ultimately create a cycle of continued social dissociation.

Such a result is the consequence of poor communication and a lack of care for the public’s perception — these disconnections are ultimately and entirely avoidable. When tactile social measures are not taken, however, resistance and ideological opposition are then experienced on behalf of both parties. This resistance is, as Foucault further explains, “never [an] exteriority in relation to power”, meaning that resistance is not only a response to power, but the natural result. From this, we should deduce that those responsible for managing the populace’s perceptions — in this case, the analysts — must present their work in a manner that not only expedites an understanding of the information, but also lowers social barriers, ultimately making the person responsible for the work perceivably more accessible to the audience. How does one go about doing so?

Through the sociological lens, these hesitations to trust the numbers can also be understood as the product of an ideological resource conflict. In this context, we are all in competition with one another for control of a resource — more specifically, control of the status quo. Each of us, and the ideological in-groups we belong to, seek to maximize the influence and prominence of our ideas such that those ideas can survive and spread for as long as possible; in a manner much the same to how biological organisms are subject to Darwin’s idea of natural selection, our ideologies and the in-groups which are created around them are also subject to a sort-of Social Darwinism. By this comparison, we can come to understand that an ideology that aims to sustain must adapt in its approach to communication and capture as many minds as possible such that it maximizes its probability of survival.

Darwin’s Finches — best known as the group of birds in the Galapagos Islands which heavily informed Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Just as two birds on a branch fight for individual territory, we compete for occupancy in the minds of the public. As H. Tajfel and J.C. Turner explain in their 1979 article, An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict, disagreements and subsequent discrepancies between groups arise “when [those] groups compete for the same resource [because] they are perceived threats to the groups’ status and power.” It is for this reason that conflicts between disagreeing groups on this matter occur so frequently; the mere existence of an opposition is, in and of itself, an innate detraction from one’s efforts towards ideological survival.

Humans are innately prone to biases, and while the already-discussed technical and sociological lenses certainly construct a foundation in answering the initially-posed question of data distrust, our approach to an answer is, perhaps, most strongly rooted in the discipline of psychology. By means of the psychological perspective, we can understand that heuristics and the innate cognitive biases derived from our mental conceptualization of the world are determining factors in the populace’s distrust of data — as they are in ultimately anything one does not intuitively understand to be true. The push to shift this ideological paradigm of skepticism is, in totality, an uphill battle against human nature. In their 1974 article Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman explain that humans are “reliant on a limited number of heuristic principles which reduce the complex tasks of assessing probabilities and predicting values to simpler judgmental operations.” To their point, we are constrained by the heuristics — or mental shortcuts — that we use in everyday life; and even if these shortcuts do allow us to simplify and make sense of a complex world, they ultimately lead us towards incomplete and, often, incorrect conclusions.

This aforementioned “uphill battle” is not solely a matter of heuristics and biases, however, as it is — of course — multifaceted and influenced by, what Tversky and Kahneman referred to as, the “initial value”. They defined this concept as a mental starting point — the preconceived notion — from which people then slowly deviate as new information is introduced. In practice, our estimates “[start] from an initial value that is adjusted to yield the final answer. The initial value, or starting point, may be suggested by the formulation of the problem, or it may be the result of a partial computation.” Just as Tversky and Kahneman posit, our pre-existing conceptualization of an idea is what ultimately rules our perception of that idea, as even when new information is introduced and adequately processed, we are still agnostic to the original conceptualization, merely deviating from an initial value. This starting point, which ultimately serves as a mental anchor of sorts, is — in part — why we so often fall victim to confirmation bias and so often observe illusory correlations. If we want something to be true, especially if we perceive that idea to be true, it becomes very difficult to deviate from the initial value to such a magnitude that we longer maintain such a perception — it is, truly, an uphill battle.

There is, lastly, a psycho-evolutionary component that is integral to the construction of these innate notions — the unconscious. While it is indeed difficult to overcome the biases of that for which we are aware, it is infinitely more difficult to deviate from that which exists in the back of our minds. Not only do these seemingly-intuitive biases have much lower barriers to operational access, but they also occur much faster and are therein more difficult to prevent. Innately, it is easier to use our intuition; and from an evolutionary perspective, it is also far less resource-intensive than executing an in-depth analysis. As Gerd Gigenrezer explains in Gut Feeling: The Intelligence of Unconscious, “people use their instincts because [they] have evolved over time to help us … make quick decisions”, which ultimately keep us alive as “unconscious processes are … much faster than conscious deliberation.” To Gigenrezer’s point, it is perhaps better to be quick and wrong — having at least executed an action — than to be slow and correct, but dead. When not in immediate danger, however, we are afforded time to deliberate, and as it pertains to the understanding of quantitative insights, we should take the time to challenge our preconceived notions; we should take the time to deviate from what we think we know to be true; and we should aim to be more correct in an effort to better understand the world within which we exist. The psycho-evolutionary perspective would posit that people are hesitant to draw their conclusions from and give their trust to data because they are slow to adapt, and because the previous means by which they reached conclusions were effective enough — fine; but just because the status quo is good enough does not mean we should not or cannot strive for something better.

To answer the question of why so many still struggle to trust the numbers is ultimately a matter of understanding human nature; it is a matter of understanding that humans cut corners and that we cheat; it is a matter of understanding that we will believe what we want to believe even if that belief does not hold true; above all, however, it is a matter of reconciling with the fact that despite inventing the computer, despite formulating cures for deadly disease, and despite pushing the bounds of what we know to be possible, we are still imperfect creatures. We distrust data not because it is right, not because it is what will drive progress — doing so will guarantee quite the opposite, in fact — but because we are in an ever-lasting search for the path of least resistance. We want things to be easy because to be easy is to be certain and stable, and humanity is fragile — our existence is delicate.

As it is, there will always be sects of civilization that disagree, and much the same there will always be a pro and an anti as it pertains to the perception of data and analytics. Nonetheless, bridges are meant to be crossed, and minds are meant to be changed — evolution is the driving force of survival, and in our pursuit to preserve our ideologies, we shall seek to understand just as we do to be understood. Perhaps we may draw closer along the way.

Comment section