PULSE Workload Blog: Pro Relief Pitcher

DISCLAIMER: At the time of usage and data collection, PULSE was known as Motus. We will be referring to it as PULSE throughout this blog.

Previously, we explored two different quarantine training scenarios for starting pitchers and the impact each might have on those pitchers’ abilities to return to in-game action (Part 1 and Part 2).

In this blog, we will look at the impact of workload on relief pitchers.

Evaluating Workload: Relief Pitchers

When evaluating a relief pitcher’s workload, it is important to account for the various ways they are utilized in games. A relief pitcher’s outing could span anywhere from a single inning to three or more. Fortunately, most pitchers at the major league level fall into only one of those categories.

Very rarely would you see your closer throwing 5+ innings in a game. For this blog, we will designate relief pitchers to one of the three following categories:

- Short Relief: Less than five batters on average (~1 inning)

- Middle Relief: Between five and eight batters on average (~1-2 innings)

- Long Relief: Greater than eight batters on average (~3+ innings)

The line can be less clear between short and middle relief and between middle and long relief. Throughout the course of a season, pitchers will very likely make outings of multiple lengths. This can occur both out of necessity and also due to performance; a pitcher who has given up 5 runs in an inning will not stay in the game simply because “he usually throws 3 innings.”

Another factor we must take into consideration with relief pitchers is their pregame routine. Unlike starting pitchers, relief pitchers do not have the luxury of knowing which days they will throw in games. The amount of pregame throwing and work on the mound between outings will vary between each pitcher and likely between each outing. A pitcher who has not appeared in a game in ten days will be more likely to throw a bullpen before the game than the pitcher who has appeared in three of the last four games.

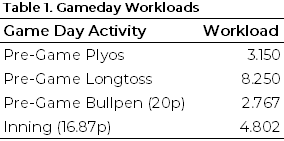

We can also reasonably assume that a reliever who throws four innings will have a different approach to the following day than the reliever who threw only one inning. For this reason, we will make a few assumptions about the throwing habits of our three different relievers. These workloads are based on averages for athletes we have had in-gym. Furthermore, these workloads, specifically Plyo Ball ® and long toss, have been modified per what we typically suggest for an in-season reliever. We still recommend using your own personal throwing workloads when possible.

Short Relief

The first scenario we will look at involve short relievers. This group typically faces five batters or fewer—think of your typical closer or setup man. It would be rare for these pitchers to have an extended appearance, outside of the playoffs. While it is more prevalent in college for closers to throw extended innings during a midweek game, that is not the case in professional baseball.

Below, we will look at the impact of various chronic workloads on a relief pitcher’s ability to make multiple appearances in a week (with a day or more off between each) and make consecutive appearances.

Multiple Appearances

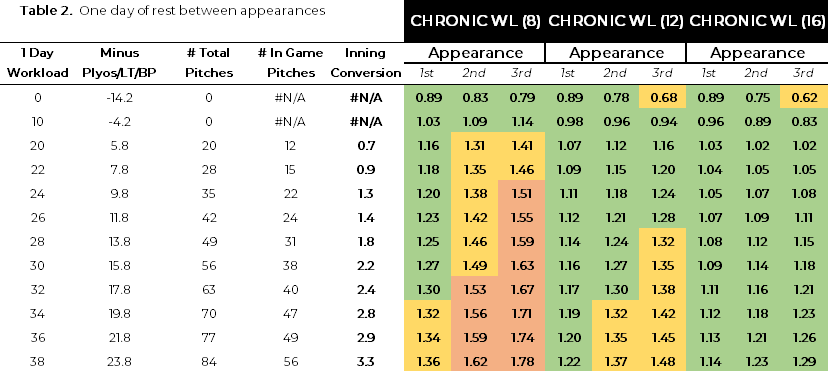

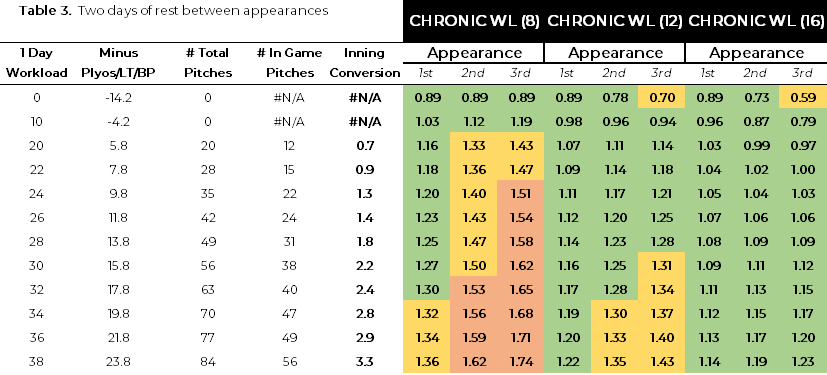

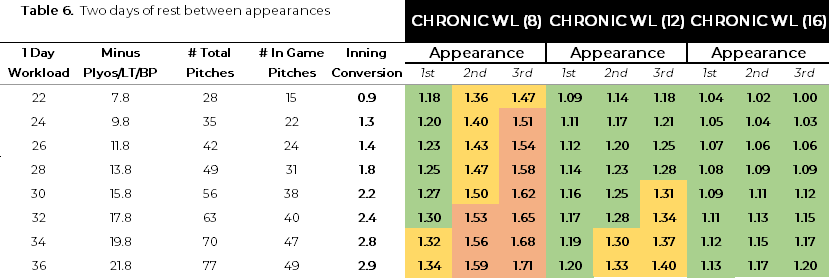

Starting with multiple appearances in a given week, we will look at the difference between one and two days between in-game outings based upon varying chronic workloads (Tables 2 and 3).

We see the biggest differences in the resulting ACRs during the second and third appearance, regardless of rest between outings. In this instance, the workloads on days that the pitcher did not throw in the game were equivalent to their pregame workload on days that they threw in the game, minus the bullpen and in-game workload (11.4 workload units). This was meant to mimic more closely the reality of life as a reliever, where you do not always know if you will throw or not and need to be ready every day. Changes in throwing workload based upon the previous day’s workload would result in slightly different ACRs; however, the current example still illustrates how greater chronic workload would allow for relievers to make more appearances within a given week.

The actual number of in-game pitches and innings is dependent on a variety of factors, such as the athlete’s individual pregame workload (including warming up in the bullpen), in-game outcomes, and the number of warm-up pitches between innings. That said, we can generally conclude that a higher chronic workload would allow a reliever to make multiple appearances within a given week.

The difference between one and two days of rest between outings is most pronounced following the second and third appearances. While an additional day of rest may not result in a large difference in in-game workload, there does appear to be a substantial difference between the resulting ACRs of these outings. An additional day between outings could also allow pitchers to modify their daily workload on days when they know they will not throw in the game. This could lead to an ability to withstand higher in-game workloads with only moderately higher chronic workloads.

Consecutive Appearances

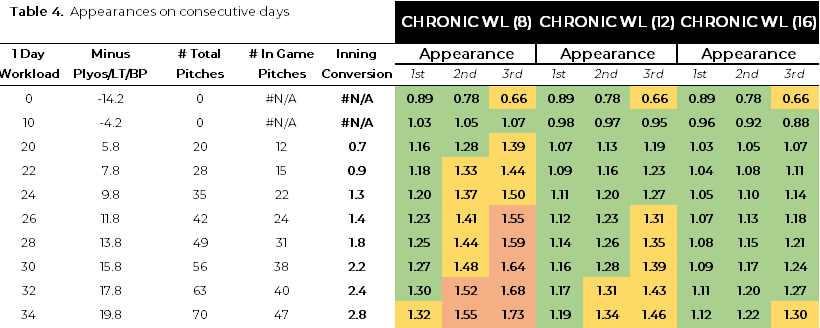

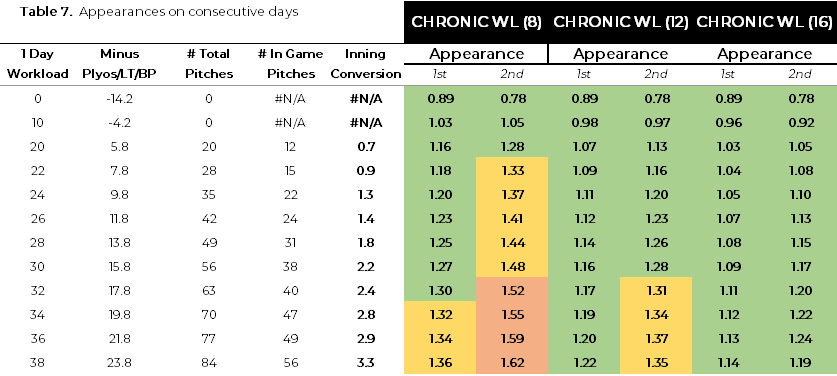

It is very unlikely that a team would never use their short relievers for consecutive appearances. In the table below, we can see the difference in resultant ACR between various chronic workloads.

A pitcher with a chronic workload of 8 workload units could conceivably throw back-to-back days with a one-day workload of 20 workload units without their ACR rising above 1.3. While that same pitcher would not make three consecutive appearances, a pitcher with a higher chronic workload could.

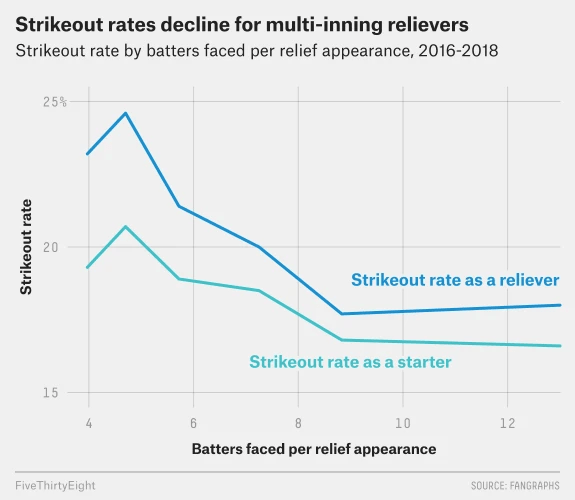

Another factor to consider is the effect throwing more can have on a pitcher’s performance. In some instances, your closer may be extremely good at their current role, but asking them to throw 2-3+ innings is not worth it due to the decline in performance, even if they are physically prepared to do so. As Nate Silver has mentioned in the past, there is a decline in strikeout rate for relievers based upon appearance length.

Having your closer, who typically never faces the same batter twice in a given game, go through the order multiple times could very well result in less desirable outcomes. While this is certainly not a guarantee for every reliever, it is something that teams will very much consider when contemplating novel ways of utilizing their relievers.

Early in the season, teams are likely to be more risk-averse and avoid throwing their top arms on back-to-back days. As the season progresses, the ability to objectively assess various scenarios’ impact could prove extremely valuable.

Middle Relief Workload

The next group of relievers that we will look at is middle relievers. This group of pitchers typically faces anywhere from three to nine batters, depending upon the situation. Like the short relievers, we will look at the impact of various chronic workloads on a relief pitcher’s ability to make multiple appearances in a week (with a day or more off in between each) and make consecutive appearances.

Multiple Appearances

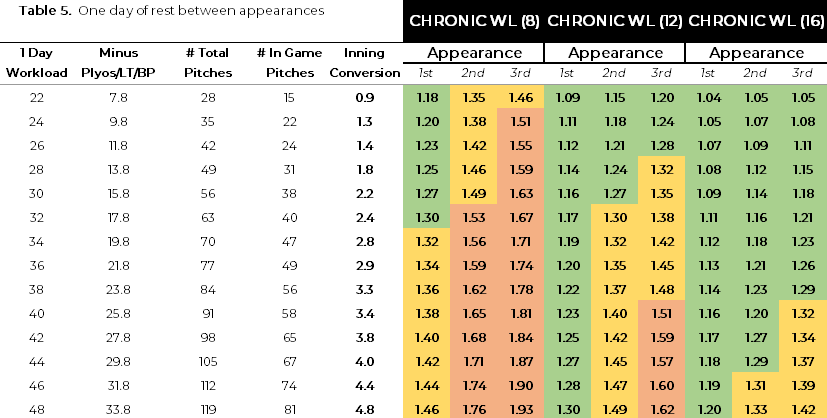

When looking at middle relievers making multiple appearances within a week, it is very unlikely that they ever throw less than one inning. There are obviously outlier instances where this does not hold true, but in this instance, we will look only at appearances between one inning and three innings. When considering multiple appearances within one week, we will look at both one day and two days of rest between outings (as shown in Table 5 and 6).

Consecutive Appearances

Next, we will look at consecutive appearances for this same group of pitchers. In the previous examples, we have examined the resulting ACR after each of the first three appearances. When discussing this subset of pitchers, we would rarely see them throw on three consecutive days (at least during your average week of the season), and for that reason, the third appearance has been omitted. That said, in these examples, pitchers are performing three consecutive days of the same workload. During the season, a pitcher is likely to make varying appearances, and the corresponding one-day workloads are also likely variable. For this reason, it is not entirely out of the question that a reliever who is typically considered middle relief would be able to throw three consecutive days in a row.

Long Relief Workload

The last group of relievers that we will look at is long relievers. These pitchers typically face eight or more batters—roughly two to three innings at a minimum. These pitchers could throw in several scenarios, most notably if a starter goes out of the game early. We also would expect some of these pitchers to make “spot starts” in some instances. It is highly unlikely we would see these pitchers throw on back-to-back days, and for that reason, we will look only at multiple appearances within a week. This will include one, two, and three days between outings at varying one-day workloads and varying chronic workloads.

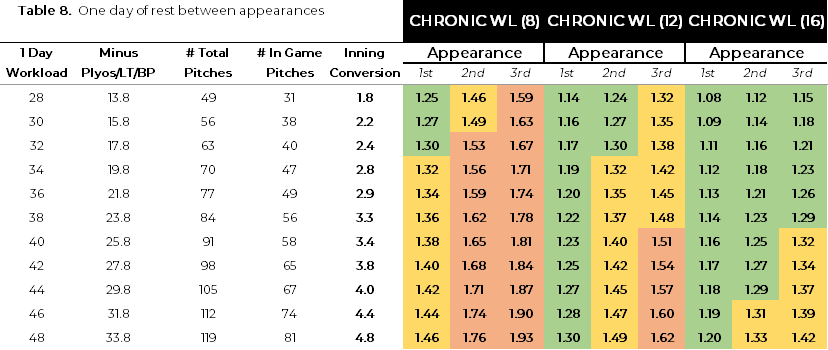

Multiple Appearances

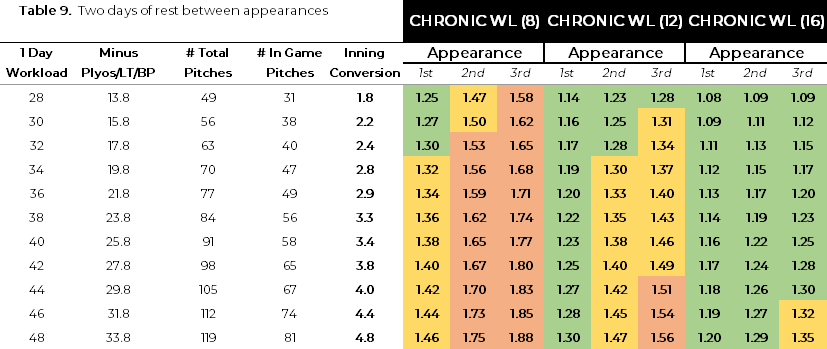

The first scenario we will look at is one day of rest between outings. This is the least likely of the scenarios for this group of pitchers. Because we typically see these pitchers throw across three or more innings, it is typical for them to receive more than just a single day of rest. As you can see in Table 8, the corresponding ACRs increase as one-day workloads increase. This holds true for all three chronic workloads. We can also see that unless the pitcher has a shorter outing or has accrued a higher chronic workload, it is likely unwise they should throw on only one day of rest. Looking at this same group of pitchers after assuming an additional day of rest between outings, we see a few differences.

The majority of differences are seen at the highest chronic workload. Still, we also see that the additional day of rest would allow this pitcher to make a third shorter stint with a chronic workload of 12 workload units. While this additional day of rest has not allowed for a substantial increase in outings per week, it did result in a reduction of the change in workload from week-to-week. In other words, we see lower ACRs for the same one-day workloads.

The last scenario is likely the most common when discussing long relievers, as they can go three or more days between outings pretty regularly. In this instance, these pitchers would have three days in between outings. For this example, these pitchers followed their traditional pregame throwing workloads minus bullpens. In reality, we may expect to see some pitchers decrease their throwing volume the day after or even add an additional bullpen on the second or third day of not throwing in a game.

Conclusion

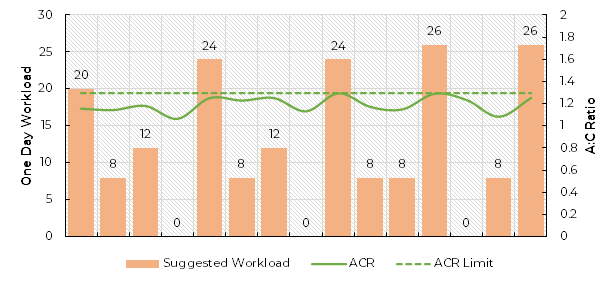

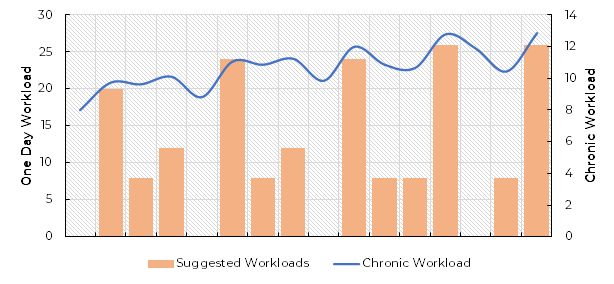

Fortunately, if you are a pitcher who is concerned that you may not have accrued the necessary workload to withstand the rigors of a season, there are still opportunities for you to make changes. Below is an example of how you could strategically suggest and program-specific one-day workloads to achieve the desired outcome. Within each of those suggested one-day workloads, you would also want to provide guidelines on the peak intensity for that given workout and the primary focus of that day (command work, competition, on-ramping, etc.).

It’s also worth noting that in these examples, we are exploring the “limits” of each of these groups; in reality, you will not be looking to push your athletes to increase their workloads consistently endlessly. Throughout the course of a season, pitchers will take on various roles, and objective workloads allow for adjustments to be made on the fly. Haven’t thrown in a game in almost a week? What is the ideal workload to allow you to get some work on the mound—maybe even facing hitters—while simultaneously staying fresh enough to perform when your name is called? These are the types of ways that coaches and players can leverage this information to their advantage.

Now, I understand that initially, pitchers might not be fond of the idea of a team monitoring their workloads. There are genuine concerns that teams could use this information to reduce in-game usage and in-game usage, and the resultant performances are obviously highly linked to a player’s contract. That said, monitoring of workload could certainly be mutually beneficial.

Teams have invested in their players and want those investments to be fruitful. Players want to play. Monitoring workloads could provide players value by increasing their in-game usage through modifications to their pregame and between outing routines. This also provides value to the players by reducing the number of times they compete in a fatigued state, which results in a higher risk of injury and reduced performance.

The team gains value through more efficient in-game usage of their top assets. This is not to say that instances like the playoffs will not still occur, where athletes and teams are simply more willing to accept greater risk. That said, this discussion only becomes possible with the use of technology that provides objective feedback regarding workloads, allowing teams and players to make more informed decisions.

By Devin Rose

Comment section