Youth Injury Series: Spondylolysis

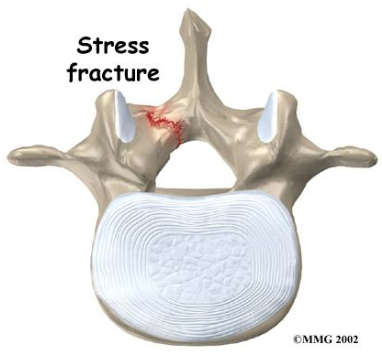

In previous posts, we have discussed chronic overuse injuries to the upper and lower limbs. The last area of discussion in regard to common youth injuries is stress injuries to the lumbar spine. The main injury of focus is spondylolysis, more commonly known as a stress fracture or stress reaction, and is defined as “a weakness or stress fracture in the bony arch of the vertebral body.”

Back pain is a common occurrence in youth athletes. It has been reported that 2-4% of athletes between the ages of 11 and 13 and 12-20% of athletes between the ages of 14 and 17 report some form of back pain throughout their playing careers. Among those athletes with pain, 40-50% will have spondylolysis. However, it should be noted that spondylolysis does not always manifest with back pain, so a reported incidence rate based on back pain may actually under report the true prevalence of this type of injury.

Several risk factors may lead into a youth athlete developing spondylolysis at some point in their playing career. First, it is important to note the anatomy of the lumbar spine. The articulating surfaces in the lumbar spine orient in a way that makes the lumbar spine more built for bending forward and backwards, and not for rotation. When participating in a sport that requires high amounts of rotation—such as baseball, golf, or hockey—the vertebral arch endures more stress. Other risk factors for spondylolysis include high-training volume, which can include too much time spent training or training at too high an intensity. In addition, an athlete who demonstrates poor strength and body control, especially in the trunk and lower body, is also at an elevated risk for developing this injury. With these known risk factors, baseball has a higher incidence rate of spondylolysis than other sports. Given the high amount of rotations made in a practice or game, the number of games or practices in the course of a year, and the fact that much of this high workload happens during developmental times when youths do not have the physical capacity to handle such a workload, these factors can create a “perfect storm” for athletes to develop an injury.

Several signs and symptoms can occur with spondylolysis. The most telling sign is pain in the lumbar spine—in particular, pain with spinal motions. Restrictions may be present in one or multiple directions of motion. The most common directions with restrictions or pain are bending backwards and bending backwards with a side bend in either direction. Because pain is not always present, athletes should be observed for other symptoms including nerve tightness, specifically in the sciatic nerve going down the back of the leg, which can appear as hamstring tightness. Other symptoms include hip tightness, decreased latissimus dorsi length (which can present as loss of overhead motion), and a loss of muscle recruitment in the muscles of the lower body. Now, the presence of one of these signs does not confirm an injury to the spine, nor does the absence of one of these signs confirm that there is no injury. Rather, these signs should be looked at in clusters where the more signs present, the higher chance there may be an injury to the spine.

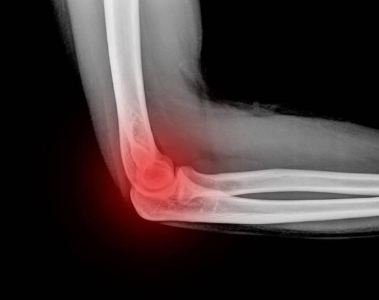

Spondylolysis can only be officially diagnosed after proper imaging has been performed. In some instances, x-rays or MRIs may be used. However, especially when dealing with smaller stress reactions, these tools may not provide the most accurate answer to the severity of a spinal injury. The two most accurate tests a doctor can perform are a CT scan or a bone scan. It is important when discussing with your doctor to get an understanding of what type of imaging is preferred and why.

Depending on the severity of the injury, there is a wide range of time needed to take off from sport. In instances of stress reactions, where the bone has begun to weaken but has not yet fractured, it is recommended an athlete take off 1 to 3 months to allow the bone to heal. If an athlete’s spine gets to the point of being fractured, the recovery time may be upwards of 6 to 9 months. Recovery time depends on the severity of the fracture, the athlete’s doctor’s preferences, and the health of the athlete. In many instances, especially when a fracture is present, a brace may be recommended to help with the healing process. For both stress fractures and stress reactions, in addition to rest from sports participation, physical therapy will likely be recommended to address core and overall weaknesses, limitations in spine and hip mobility, poor posture, and body awareness. Generally, physical therapy will take place throughout the entire recovery period, and the therapist will guide the athlete through a gradual return to sport protocol.

Improper treatment of spondylolysis can have severe, lasting effects. The biggest of which is the potential of developing chronic back pain, not only throughout a youth’s playing career but also well into adulthood—even if the bone does fully heal. Other potential implications can include chronic or ongoing injuries to the lower body or, in more drastic cases, can indirectly lead to injuries of the throwing arm. With all the possible long-term consequences, it is important an athlete gets properly diagnosed in a timely manner and works with a physical therapist to address any deficits that may have lead to the injury in the first place.

While spondylolysis is not completely preventable, steps can be taken to reduce the risk of incurring an injury. Similar to the injuries we’ve discussed in previous posts, monitoring the intensity and frequency of sports’ participation year-round is of highest importance. Parents and coaches should take note of fatigue in an athlete. This not only includes subjective complaints of fatigue but also noting decreased performance, complaints of back tightness, or even loss of flexibility in the lower extremities. If athletes are competing at a high level of intensity, they should also participate in some type of strength and conditioning program to address any strength, flexibility, or motor control deficits that may be present.

As the intensity of youth sports continues to grow, so does the prevalence of spondylolysis in this population. The potential of this injury to have career-altering and long-lasting effects makes early detection and treatment extremely important. With proper preventative measures, screening, and treatment, the effects of this injury can be drastically minimized and athletes can continue on with long, healthy playing careers.

References:

Bono, Christopher M. “Current Concept Review: Low-Back Pain in Athletes.” Journal of Bone And Joint Surgery, Incorporated, 2004, pp. 382–393.

DiFori, John P, et al. “Overuse Injuries and Burnout in Youth Sports: A Position Statement From the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 48, 2014, pp. 287–288.

Lawrence, Kevin J., et al. “Lumbar Spondylolysis in the Adolescent Athlete.” Physical Therapy in Sport, vol. 20, 2016, pp. 56–60., doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.04.003.

Looper, Mark, and Ken Cole. “CORE-Tical Control: Linking The Extremities H Through Neuro-Muscular Control.” Kirkland, WA.

Muller, J, et al. “Back Pain Prevalence in Adolescent Athletes.” Scandanavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 27, no. 4, 2017, pp. 448–454.

“Spondylolysis in Young Athletes.” Physiopedia, www.physio-pedia.com/Spondylolysis_in_Young_Athletes

Comment section