Scaling Velocity & Useful Spin in Offspeed Pitches

We still don’t know a whole lot about spin rate. While we certainly know more about how to use it under certain situations, we don’t know that much on how to develop better spin.

Because of this, we are running smaller experiments to get a better idea of what to test and what to look for.

The idea is that smaller tests lead to bigger samples that lead to better understanding and, in the end, better athlete results.

First, let’s recap the things we do know about spin rate before looking at our own data.

What We Do Know

For four-seam fastballs, it’s pretty straightforward. High-spin fastballs result in more flyballs and swing-and-misses and are more valuable thrown middle up in the zone. Low-spin fastballs result in more ground balls and are more valuable thrown down in the zone. If you have an average spin rate, your best bet is going to be learning a two-seam.

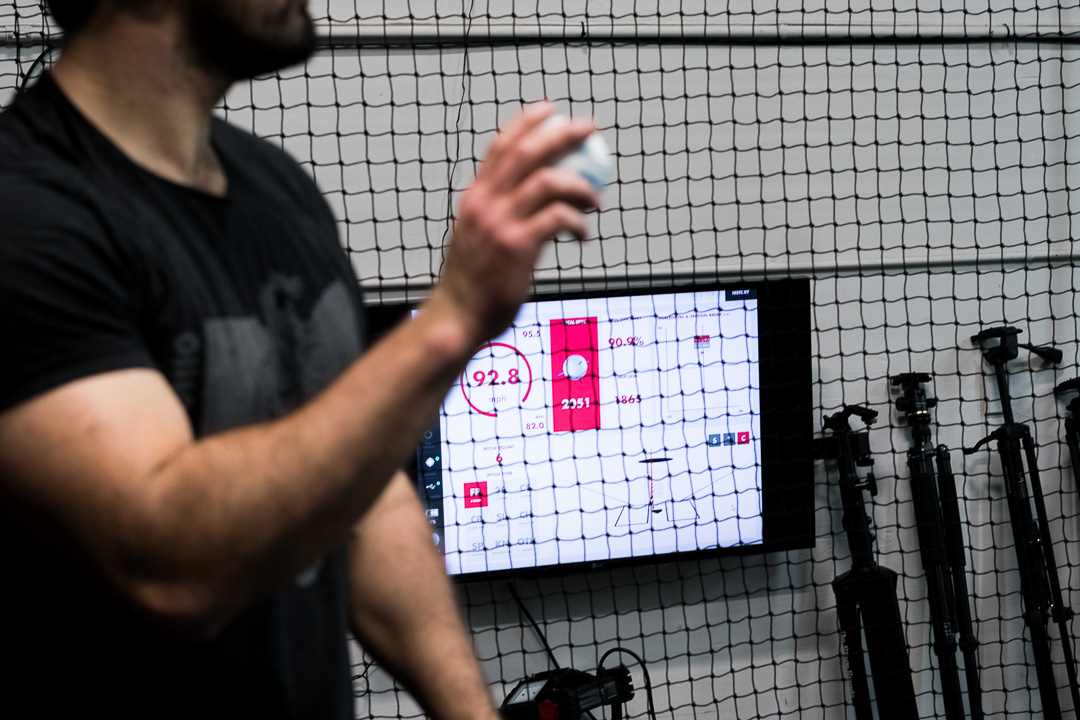

For offspeed pitches, it gets it bit more tricky. We can say that having a high-spin offspeed pitch is generally a good thing. But the useful spin, or spin aligned with the axis of the ball, is of more use than the total spin. Now, the numbers we get from MLB can’t give us the useful spin, but we can get a useful spin reading using a Rapsodo.

So what can the Rapsodo show us about useful spin in offspeed pitches when trying to practice them?

We wanted to replicate different practice situations, throwing curveballs and sliders at low intent off a mound and on flatground, to see if the useful spin would change when compared to pitching at 100% intent.

We are trying to answer the question: What is the best way to practice offspeed pitches to make them better in a game?

In this study we’ll look at total and useful spin before focusing in on the useful spin, or spin-efficiency number. Spin efficiency is the percentage of spin that is lined up with the axis of the ball. While true spin or useful spin is the RPM of spin lined up with the axis of the ball.

Our Data

We used a few athletes and a couple employees on throwing programs to throw offspeed pitches for this study. We had each athlete warm up and throw five offspeed pitches at 100% off a mound, then five offspeed pitches at 75%, followed by five throws at 75% from flatground. We used the Rapsodo, which we’ve previously validated to Trackman readings, to measure ball spin.

We split up the pitches to sliders and curveballs, and here is what we found looking at velocity, total spin, and true (useful spin).

Note: Pitcher 3 throws from a lower arm slot. So his curveball is more of a slurve, where pitchers 1 & 5 throw more over the top.

While this isn’t enough to make sweeping conclusions, it’s important to look at some of the individual differences. We aren’t sure why these differences occur, but the best guess is that athletes all downregulate their throwing motions in different ways. This alone might be enough evidence to suggest that practicing offspeed pitches is not a “one size fits all” program.

It’s important to realize that with curveballs you generally want a high-spin efficiency, so a higher true spin. With sliders, you are looking for a low-spin efficiency. This can be confusing, but comparing the true spin of curveballs and sliders will help put this idea into perspective.

The data for both charts can be found here

This is a lot to look at for a small sample size. We can see the drastic differences between the Units and useful spin of curveballs compared to sliders. Second we can see that some of the differences in spin efficiency can be pretty drastic and individualized.

Remember, the goal of practice is to get better at a skill. We can look at the differences in spin efficiency and think:

If we are practicing offspeed pitches at a different spin efficiency, are we truly practicing to get better at that pitch?

Although we don’t have the current ability to measure release point, we can suggest that the changes we see in useful spin are because the release points or wrist action change slightly. This goes back to the idea that pitchers don’t repeat their mechanics exactly the same for every throw. These slight changes increase when we tell athletes to slow down their mechanics. Each athlete will throw at lower intent in a different way.

Also, we have moved away from most flatground work. We found the differences in elbow stress to be minor compared to the differences in velocity. So even though current research supports the idea that there is little difference between elbow torque of fastballs and offspeed pitches, there are still workload concerns in throwing a lot of flatgrounds.

Plus, there is not a direct transfer between having good mechanics on flatground directly correlating to good mechanics on the mound.

This isn’t to say that flatgrounds don’t have any place in practice, but they are often overused. We can all remember the teammate who “one more his way-ed” to 10 more sliders on flatground to get the movement right. This isn’t going to be a beneficial use of an athlete’s training economy.

Developing Pitches

Now it’s important to note that we’ve been discussing throwing offspeed at different levels for the purposes of development, which is different from preparing for a game.

If athletes are warming up for a game and have a specific routine, they should continue to experiment with what makes them feel comfortable and the most prepared.

But when you are trying to develop a pitch, this data pushes us to the idea that we should stay away from extensive offspeed-pitch practice at low intent from flatground or the mound.

This is for two reasons, first flatgrounds are more stressful than believed, meaning you are incurring a higher training cost than you are accounting for. Second if the useful spin is different, you probably aren’t practicing throwing a pitch the same way it’ll be thrown in a game.

This requires us to look closer at our own programming, but we are aiming to create more time for athletes to throw in game like scenarios with real time feedback from the technology we provide.

We use both the Rapsodo and high-speed cameras to develop pitches. The Rapsodo gives us feedback on the velocity, spin rate, spin axis and useful spin. While our cameras, mainly Edgertronic, give us a glimpse of how small grip and finger changes affect how the ball comes out of the hand.

Now not everyone is going to be able to use buy an Edgertronic, but there are still other cameras that can be helpful. Here is an alternative that we would recommend.

Improvements to this study may include:

- A larger sample size of participants

- A more elite group of pitchers at higher velocities

- A larger sample of throws per athlete

- Reversing the order of the throws from flatground to the mound

This article was written by Research Associate Michael O’Connell

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe -

Very cool. When you talk about sliders having less spin efficiency, you’re stating that the axis and the spin shouldn’t match each other?