Can the starting pitcher be revived?

The Pitching Paradox

It was once commonplace in Major League Baseball for a starting pitcher to go seven innings and throw 100+ pitches. Turning on a Sunday Night game, you would expect to watch two workhorse aces duel for eight innings before relinquishing the ball to the bullpen. Nowadays, it’s a rarity to see starters surpass 100 pitches in a game, with fewer eclipsing the 200-inning mark. On a perhaps somewhat related note, MLB has also experienced a spike in pitcher injuries, namely UCL tears and subsequent Tommy John surgeries.

The arm injury paradigm has been a hot topic for more than a year now. Many are quick to point to the year-over-year rise in average fastball velocity, suggesting that an increased intent to throw hard is the primary culprit behind the rise in injuries. Oddly enough, these folks likely aren’t entirely wrong—throwing is innately stressful and throwing hard requires an immense production and transfer of force. If you want to be successful in today’s Major League Baseball, throwing hard is non-negotiable.

However, just because higher pitch speeds correlate with higher injury risk does not mean we should forgo that risk entirely. Instead, we need to better understand it, optimize it, and implement training methods that keep pitchers on the field while still allowing them to throw harder.

Aside from injury, often lost in conversations about the “good ole days” of starting pitchers working deep into the night is the impact on their effectiveness the next time out. On those same Sunday Night Baseball broadcasts, you might hear the announcers mention the starters’ heroic complete game shutout five days ago and to be on the lookout for a “hangover outing.” In a FanGraphs Community Research article, Paul Kasinski explores this idea and had similar findings to what we intuitively know—there is a residual effect of longer outings impacting future ones.

This should not discourage pitchers from wanting to rack up innings, the ones that know how to prepare for the season and navigate the days in between outings collect a handsome reward. The goal, instead, is to understand the factors that contribute to peak performance, understand how to maintain it through a season, and recreate it across other athletes. Decrease luck. Eliminate guesswork.

This is where PULSE creates space in the discourse.

Allow Me to (Re)Introduce Myself

You’ve probably seen the pictures and videos on Instagram and Twitter of MLB pitchers with black straps around their upper forearms—that’s PULSE. PULSE is Driveline’s own wearable throwing workload monitor designed to give athletes and coaches unparalleled insight into what stress a pitcher is experiencing.

Spring Training is underway, and there's been a surge of pictures of MLB pitchers wearing @DrivelineBB Pulse sensors to camp.

It's an interesting occurrence given the discourse around workload management and pitcher injuries over the last year, so what's the deal with Pulse? pic.twitter.com/UEQNnqNO8N

— Thomas Bentley (@BentleY__ThomaS) February 19, 2025

This idea of workload management is not unique only to baseball, nor to Driveline. It is a concept as old as training. As training enters the modern age, GPS monitors used to track the distance covered and speed reached by athletes have gained prominence in other sports, such as football, basketball, and soccer. Across the college and professional ranks, teams have recognized the importance of tracking workload and fatigue, using technology to make smarter decisions about how athletes train and recover.

The difference in baseball, however, is that injuries are overwhelmingly concentrated on a single joint: the elbow. While other athletes deal with general wear and tear across multiple areas of the body, pitchers face a more localized problem. Nearly every throw made applies stress to the UCL, which is now the most talked about ligament in professional sports. Understanding how stress accumulates is critical, yet most throwing programs still rely on vague estimates and incomplete data to gauge workload. If the goal is to keep pitchers healthy while allowing them to throw harder, more precision is needed.

Traditional approaches to tracking throwing volume leave a large majority of throws unrecorded. If a pitcher throws a 25-pitch bullpen, that is typically understood to be a “high effort” day with 25 high intent throws. It’s easy to look at that number and assume that it represents the entire workload for that session. But what about the plyos to warm up, catch play to get the feel for the baseball, and throws on the mound before the bullpen starts?

The bullpen itself is not the only throwing done, but those throws historically are the only ones tracked. Without a system like PULSE, all the additional throws are invisible. A day that reads “Bullpen – 25 Pitches” can have five times the number of throws listed, not accounting for the intensity of those throws.

For the days between mound sessions, most training plans assume that pitchers execute their prescribed workout exactly as intended. However, that is rarely the case. The hidden stressors accumulate and, if they go unchecked, unaccounted for fatigue can lead to a decline in performance or even injury. The difference between feeling your best and needing a day often lies in the unseen reps that happen outside of a bullpen or game appearance.

PULSE eliminates the guesswork. Rather than relying on estimates or assumptions, it provides a complete, objective record of how much a pitcher is throwing, the total load they are under, and how their workload fluctuates from day to day. This allows pitchers and coaches to construct more precise training plans and more informed adjustments throughout the season.

What Have We Learned?

PULSE is used by both in-gym and remote athletes that train with us to track the volume and intensity of each throw they make. Using total throws, arm speed, and torque, we see each athlete’s throwing workload with clarity. This allows for better understanding the demands of the throwing programs we deliver to our athletes.

An immediate takeaway from PULSE is that throwing volume is hard to track. Manually counting the number of throws you make on the plyo wall, in catch play, during defensive work, and in warmups in the bullpen is difficult and unnecessary, nor is it feasible for a coach to do with his entire staff.

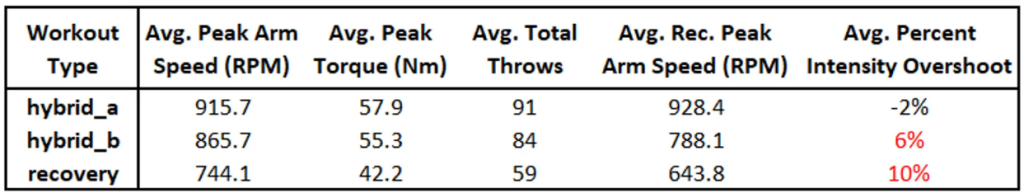

Outside of volume, we have come to understand gauging sub-maximal intensity is also hard. Intentionally light throwing days, which we call in our programming as “Recovery” and “Hybrid B” days, are only meaningful if the intensity is properly managed. Our paired use of PULSE and radar guns helped us uncover that many pitchers fail to consistently execute intensity recommendations. On days where the effort is intentionally low, it is not uncommon to see athletes overshooting the prescribed intensity.

“Recovery” and “Hybrid B” days, are critical for maintaining throwing skill and fitness while keeping the torque applied on the elbow low. Overshooting the low days leads to a larger chronic load placed on the joint, never giving the surrounding musculature time to recover.

While PULSE assisted in identifying this trend, it also allows us to make quicker interventions. Feedback and adjustments can occur on a throw-level basis helping pitchers hone their perceived effort, or feel, with objective measurables. The increase in feel leads to more throwing sessions being performed at the appropriate effort.

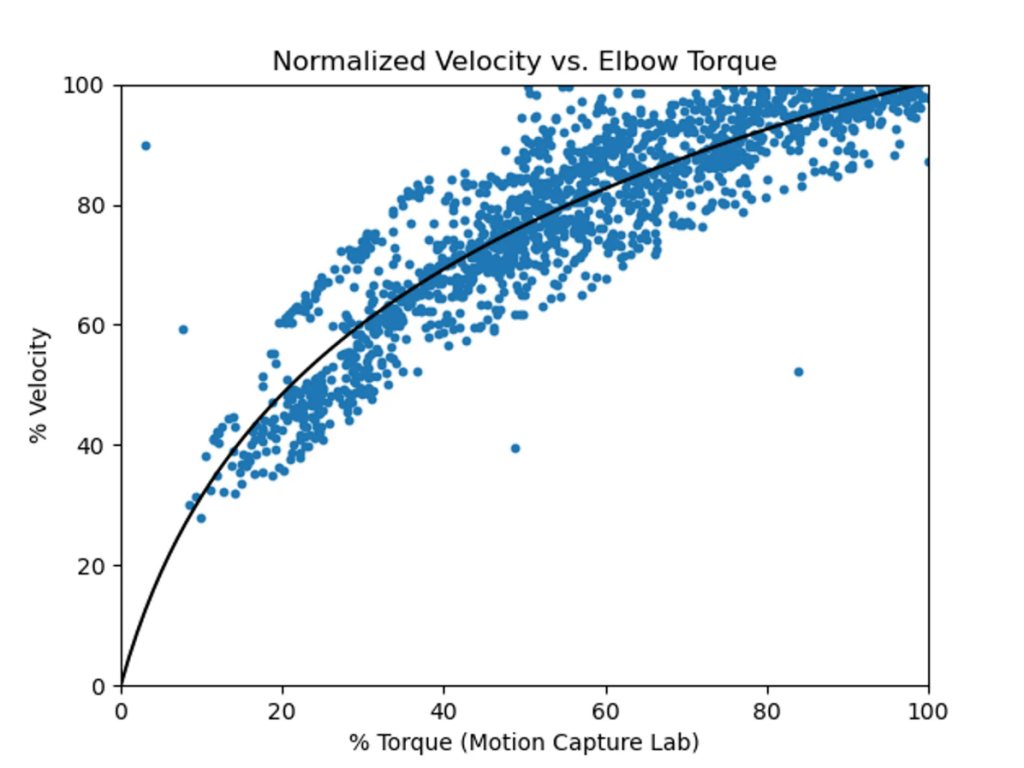

As a pitcher approaches his peak velocity, the torque the elbow experiences does not increase linearly. In fact, the relationship between torque and velocity is quite the opposite. Significantly more torque is applied the closer a pitcher gets to his peak.

This has some major training implications. On days where velocity is not the priority, small increases in velocity result in disproportionate increases in torque. Over time, the increase in total torque leads to chronic fatigue and the inability to fully recover. This only further emphasizes the need for more precise throwing programming and monitoring on the lighter throwing days.

As pitchers accumulate fatigue, the relationship between torque and velocity changes. A fatigued pitcher experiences more torque to maintain their usual level of velocity. These effects of fatigue are compounded during long innings, deep in outings, or late in a season. This is something that is intuitively understood and has been combatted with pitch counts during an inning or outing and inning limits over a calendar year. PULSE allows us to quantify the effects for each athlete and make better, more precise training recommendations.

👀👀👀 https://t.co/O8LSdJoFjf pic.twitter.com/qyCb52kPyX

— Clayton Thompson (@clayton_t22) January 4, 2025

Pitchers and coaches are now armed with the necessary information to make better training decisions throughout the year. Whether it be throwing too much or not enough, knowing when to adjust the throwing schedule or leave it as is has never been easier.

Applying the Research

Taking these insights into account allows us to design more precise training and workload guidelines. Throwing programs are traditionally built around general recommendations for effort, volume, and intensity. “Light long toss,” “touch and feel,” “side session,” and “bullpen” are all common things you will hear around practices. Each comes with an assumed understanding of how those days are supposed to be performed. With PULSE, there is less room for interpretation and better understanding of how each session is performed.

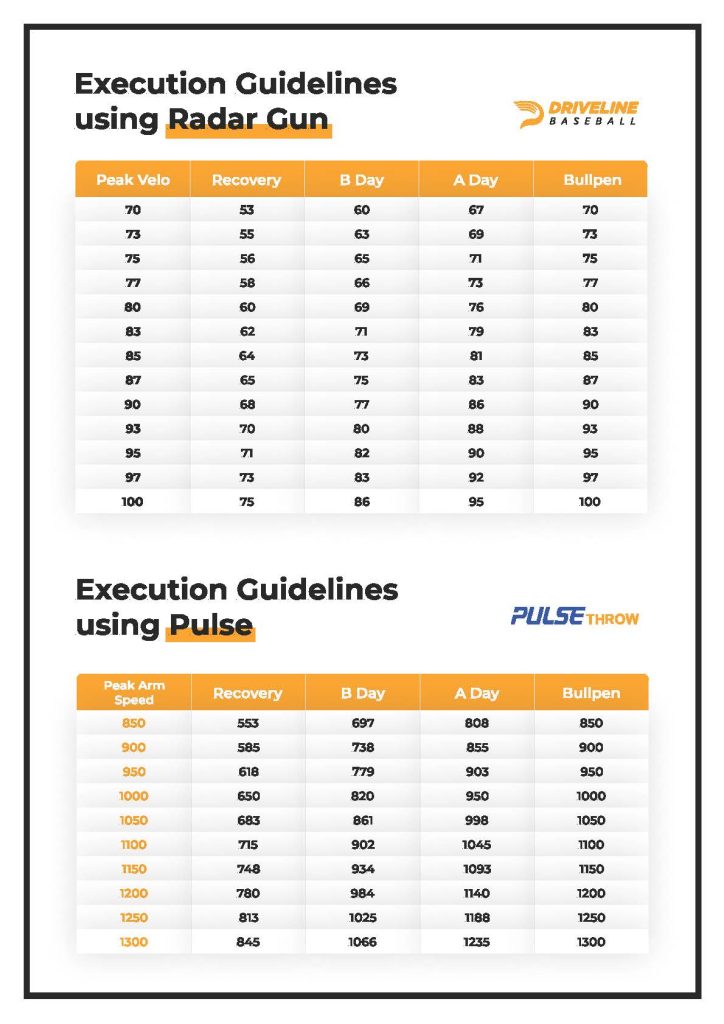

By analyzing each athlete’s playing level, peak velocity, arm speed, and throwing history, we can now prescribe individualized guidelines that provide specific, quantified targets on all throwing days. Instead of relying on vague suggestions such as “medium effort” or recommending 7-8 RPE, the athletes we train now have concrete numbers to orient themselves around. Since the 2022 Summer, an athlete training in our gyms or following one of our free programs online would see the following chart guiding you in your throwing session.

As we developed our Driveline Baseball training app, the chart went from hanging on the walls to appearing on the home screen of the Driveline Baseball Training App for each athlete. We call this tool SMART Reports. Not only do athletes get feedback on how prior throwing sessions have gone but also receive ranges for what velocity they should be working in for the upcoming sessions—PlyoCare drills included.

The daily SMART Reports we give our athletes act as a hub to provide feedback on their previous training day and set the intention for the upcoming one. The purpose of these is not to restrict our athletes or have them do less—quite the opposite actually! When it is time to perform, whether it be a Velocity Day in offseason training or Game 7 of the World Series, we want to ensure that the proper amount of work has been done to give our athletes the confidence and capability to go out and compete with mindless aggression. No worrying about “have I done enough? Too much?”—just executing the task at hand.

As coaches, we see the residual effects of fatigue too late in the process, usually in the form of decreased velocity, stuff, or command. It is only once we see the change in performance that we get the signal to look back at what the athlete has been doing to figure out what led to the decline. By having personalized recommendations and the subsequent grading of them, we can catch any potential red flags earlier in the process and before it shows up on the mound, in theory also reducing the risk of injury along the way.

We understand that not every throwing day is going to be executed perfectly. There will be days when you throw a bit too much or a little too hard. There will be days when you don’t throw enough or undershoot the intensity. The goal is not perfect execution. The goal is to improve and sustain performance. Paying attention to this information and adjusting, when necessary, ensures that short-term fluctuations do not compromise the long-term goal of improved performance in the upcoming season. There exists a Goldilocks zone—the sweet spot between too much and too little. As all levels of the game get better, that sweet spot tends to get smaller and the margin for error is already razor thin.

Back to the Future

This significant progress has only been possible because of the groundwork laid by the individuals who understood that baseball had a question worth being answered. Kyle Lindley, Kyle Wasserberger, and Anthony Brady’s research helped us understand the stresses of throwing. Devin Rose’s conceptual work (Starting Pitcher Workload: Parts 1 and 2) on the building blocks of workload and how to structure throwing programs centered around performing when it matters has shaped how we construct and adjust throwing plans. Lastly, the transition from theory to application was helmed by Kyle Boddy and Joe Marsh, who took these ideas to the field and applied them in a professional setting with the Cincinnati Reds.

The reality we face is baseball has evolved. Pitchers are throwing harder, the margins for success are thinner, and the consequences for mismanaging workload are more severe. With the right tools and insights, the pursuit of high performance and longevity doesn’t have to be a trade-off, they are something we can achieve simultaneously.

If the goal is to maximize performance, optimize injury risk, and create sustainable success, then our approach to throwing cannot remain static. It must adapt to the needs of the athletes playing the game. With better data, we yield a better understanding of how to train for sustainability and get closer to eliminating the guesswork of workload management. We can never fully eliminate the inherent risks of pitching, but there is a way to manage them better than ever before. That is the pursuit we are engaged in and that is what PULSE is designed to achieve.

“Ford v. Ferrari” plays with a concept called the “Perfect Lap”—”no mistakes, every gear change, every corner, perfect.” Christian Bale’s character, Ken Miles, is sitting with his son explaining the idea, beginning with his son asking, “You can’t just push the car hard the whole way, right?”

We believe baseball’s “Perfect Lap” is not limited to just the Perfect Game. The confluence of skill, preparation, and fortune drops jaws, leaving us fans amazed: 2015 Jake Arrieta (especially the second half—wow); the careers of Kershaw, Verlander, and Scherzer; the defying of the aging curve by Aroldis Chapman.

As the next crop of stars emerges, the already slim margin of error that this game is built on has gotten even tighter. This calls for more precision and intentionality in the way we approach offseason training, as well as the adjustments in-season from outing to outing.

So where are we going? The same place we always have been—forward. The pairing of workout, motion capture, radar gun, Trackman, and Intended Zones data allows us to quantify the acute and chronic effects of fatigue on performance and health. But that is not enough. We also must continue to push the training forward, not just at the top, but at all levels. The future of the game depends on it.

Written by Jackson Sigman and Thomas Bentley

Comment section