Optimizing for Health & Development in Youth Baseball – Part 1

Introduction

Seventeen million.

That’s the number of kids – roughly – that have stopped playing baseball between when my son started playing and today. Thanks to the efforts of the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative, we know that every year youth baseball loses somewhere between 1.6 and 1.8 million players per year in the transition from the 6-12 year old cohort to the 13-17 cohort. So from 2014, when my son suited up for his first official T-ball game, to today going into his sophomore HS season, if we just split the difference between those rough numbers that adds up to around seventeen million players that have stopped playing baseball before they got to the 90’ field.

I am very thankful that my son did not make that number seventeen million and one.

To be clear, I do not need him to play baseball just because I’m the Director of Youth Baseball at Driveline and he’s my son. The longer that he has stayed in the game, the more I have made consistently sure he understands this is solely his journey. He still wants to play the game and improve his ability on his own accord, which is the thing that I truly care about most – whether it pertains to baseball, world history, architecture or anything else that sparks his interest as he gets closer to adulthood. I broadly want him to be intrinsically motivated to follow his passions and execute them to the best of his ability, and right now his passion is aimed at baseball.

All of that said, I cannot ignore the likelihood that his wanting to play the game, and his competitive ability within the game, has been influenced by some of the choices that I made as a parent and what his youth baseball experience was to be optimized for by those choices. At this point I can clearly say that the moments that I optimized for health and development were the ones when I got it right. And the momentary moments when I strayed from that optimization is when I got it wrong.

So, what does it actually mean to optimize for health and development? To understand how to get – and stay – on that particular path we have to first define what it actually means to optimize for health & development, then define some of the choices that will have to be answered along the way to keep us there. In part 1 of this 2 part series we will focus specifically on what it means to optimize for health.

Optimizing for Health & The Youth Throwing Injury Landscape

When we are talking about optimizing for health, we are talking about keeping players in a state where they are ready to compete, in training and in games. To do this it is imperative that we understand the concept of workload.

(want a complete understanding of these workload concepts and training programs for how to apply them? Check out our book Skills That Scale: The Complete Youth Baseball Training Manual)

When we are discussing the concept of workload, what we are trying to do is put some definition around what the actual physiological effects of throwing are. It’s important that we have this understanding of the effects of throwing, because all throwing has cost:

- Catch play

- Plyocare drills

- Pitching

- “Touch & Feel” bullpens

- Long toss

- Position play throwing

- Towel drills

- Low intent throwing

- High intent throwing

- Fastballs

- Breaking balls

At different points in time some of the above throwing modalities were considered to have little to no physiological effect on the thrower, and were prescribed in training because of this belief. Thanks to newer research we understand that this is definitively not the case, because if the towel drill has costs then it is logical to extrapolate that all throwing has costs we need to account for.

Now, it is still true that these costs can be variable. For example, a casual throw early in catch play would have lower cost than a 3-2 fastball thrown in the last inning of a championship game, but the most important concept we need to understand is that all of these throws, of all sorts of intensities, with all sorts of ball weights and different amounts of volume are going to incur some kind of physical effect on the thrower.

If we are attached to the need to keep players in youth baseball healthy then it is critical that we track the costs of all throwing, specifically because of what we understand about the most common mechanisms of injury in youth baseball: players throwing while fatigued.

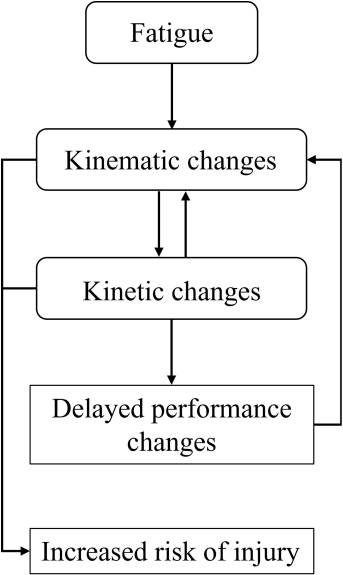

Research conducted by the American Sports Medicine Institute and the Andrews Research and Education Institute paints a very stark picture: if a young baseball player throws with fatigue there is a 36 to 1 increased chance that they can injure their throwing shoulder and/or elbow. This maps to other research on the topic of throwing while fatigued and injury risk. While the entire picture is not perfectly clear, what we do understand is a very basic relationship between throwing with fatigue, kinematic / kinetic changes, and ultimately increased risk of injury:

The “cost” of throwing is largely going to be defined by variations to the inputs – the intensity of throws along with the volume of those same throws.Throws at higher intensity are going to generally have a higher cost than those at lower intensities, but the volume of both high and low intensity throws is going to define the actual workload.

When a player throws a “low intent” mound session of 50-60 pitches mid-week leading into a tournament weekend they still need to accommodate for the workload that session created, low intensity or not. Similarly, a player who throws a mid-week 20 pitch bullpen at competition levels of intent is also going to have to accommodate for the workload that session created. Both players are at risk for having to deal with pre-event fatigue if there is an inadequate amount of time to rest and recover from those throwing sessions before they begin playing games on the weekend. And again, we know that throwing with fatigue is the most critical thing we want to avoid in order to keep players optimized for health.

We can also take some signal from this relationship between fatigue, kinetic & kinematic changes in throwing mechanics and ultimately increased injury risk to further understand the landscape of youth throwing injuries at present. MLB recently released a paper that summarizes their findings on this issue, and takes insight and opinion from a variety of sources both at the professional and amateur level for the sources of these issues. While opinions may vary on all of the factors involved, the one thing that everyone agrees on is the greatest issue is overuse. In this framework of understanding workload and the physiological effect of throwing on the body, overuse is the primary variable we need to control for because overuse inhibits players ability to avoid throwing in a fatigued state.

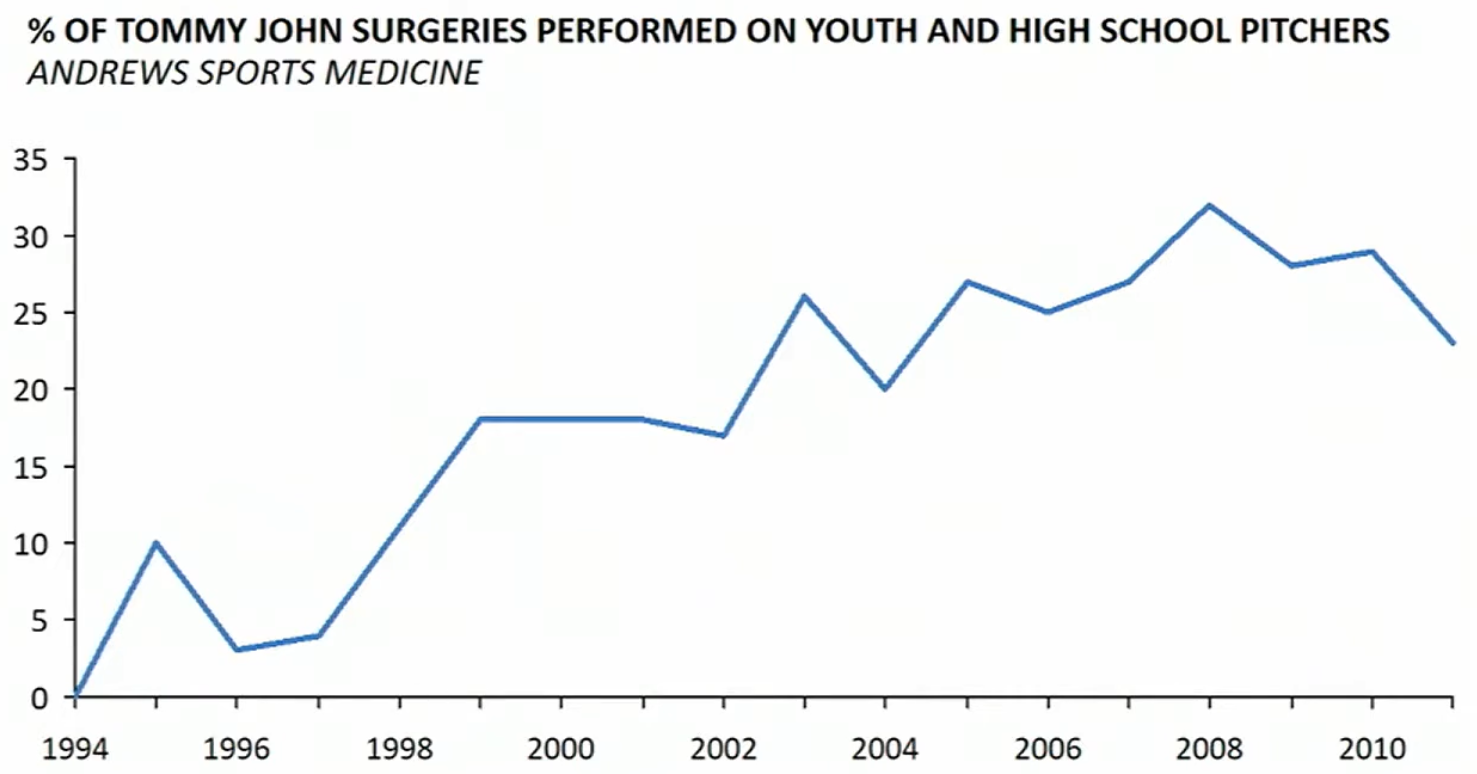

This graph showing the percentage of Tommy John surgeries on youth players performed by the Andrews Sports Medicine facility was presented by MLB’s John D’Angelo at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in 2017:

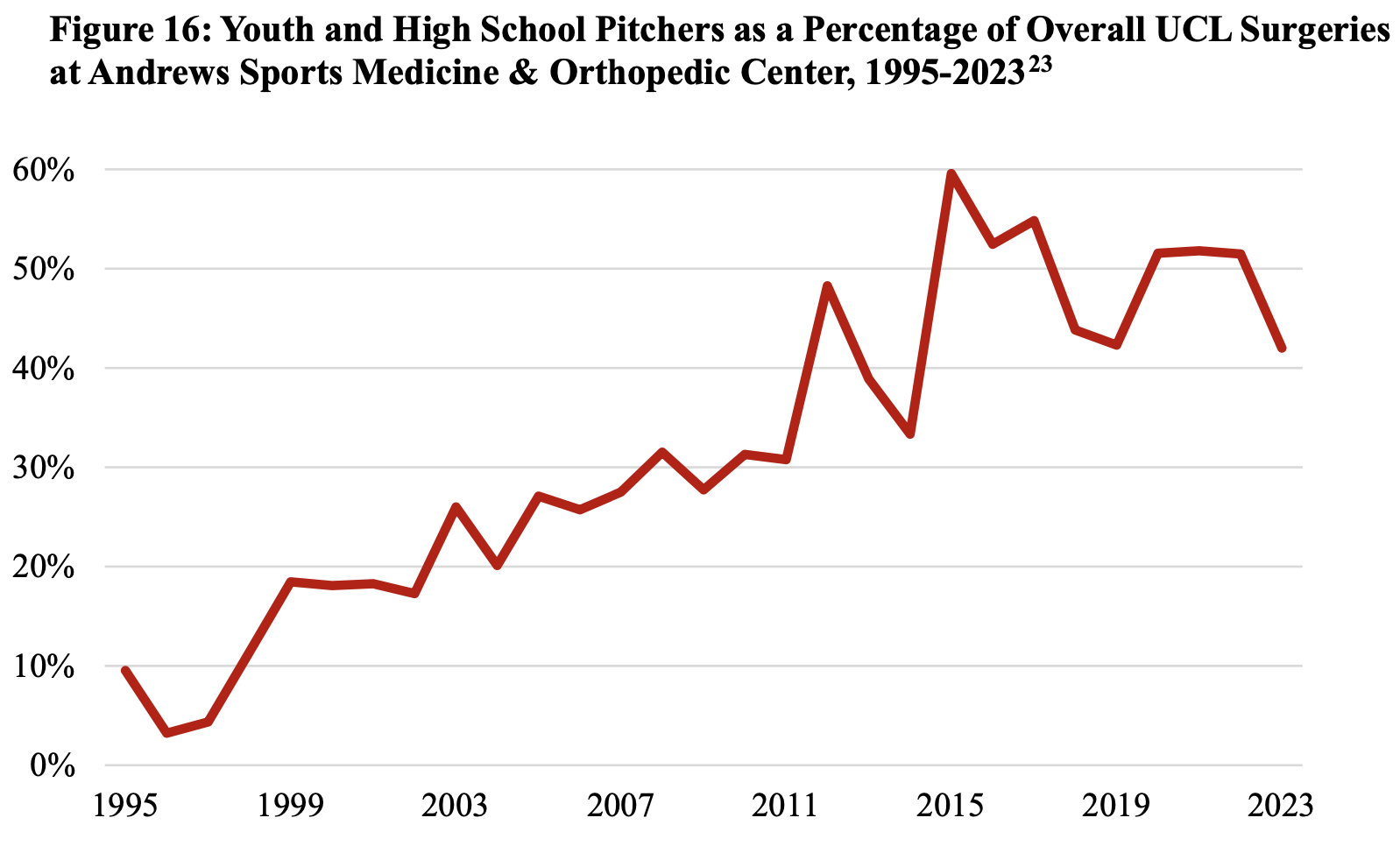

And this updated chart was published as part of MLB’s Pitching Injury Report that was released in late 2024:

Looking at these two charts we can see that since 2017 what was already an alarming trend has largely only gotten worse. While some uninformed people would suggest that Driveline and other purveyors of specialized youth baseball training are to be blamed for the current injury issues in youth baseball, it’s worth noting that the percentage of UCL surgeries they attributed to youth was already around 30% in 2009, the year that Driveline was founded. What is the one thing that has stayed constant throughout this entire period of time? An increase in the total amount of games played, which is the conduit for overuse.

Beyond this minor clarification on the “source” of the injury epidemic in youth baseball, the broad trend here should be alarming. Anytime that youth and adolescent patients represent more than 50% of the surgical population at a place like the Andrews facility we all should be justifiably concerned about why this is happening. The signal that we want to extract from this trendline however should largely revolve around not the rate of youth UCL surgeries themselves, but the behavior and underlying trends that leads to surgery being a necessary step for some players. Again, we do not yet have a 1:1 causal relationship between any specific volume of throws – or a specific workload – that leads to a player needing UCL repair. But what we do understand is the general path of behavior that leads to that surgery: throwing with fatigue can lead to injury, and continuing to throw with a minor injury can lead to a major one that may require surgical intervention.

Applying Workload Concepts For Healthy Game Preparation

When it comes to the time periods that we want to monitor throwing workload, the primary intervals we’ll monitor for the effects of throwing are:

- Acute Workload: Throwing volume and intensity from a single day

- Chronic Workload: Throwing volume and intensity over a longer period of time

- Rolling average over the past 28 days

Thanks to tools like Driveline PULSE, we can definitively measure the effect of these throws – their volume and their intensity. You can read more about the function of Driveline PULSE here, and if you are committed to getting the most actionable information on how to keep your players safe the PULSE sensor is the most valuable tool you can use to monitor the effects of their throwing. For the sake of this article however we will just focus on the variables at hand we can understand without a PULSE sensor and the simple choices we can make to moderate them to keep kids healthy.

Whether a player is healthy and ready to compete in a weekend tournament is largely going to be determined by their throwing in the week and weeks that lead up to the event. A very reasonable two week throwing program designed to get players ready to compete in a healthy state might look something like this:

It’s worth noting that this is a very abbreviated schedule for throwing, and that what’s truly going to affect a player’s throwing readiness going into a weekend worth of competition is not only these two weeks, but all of the weeks previous. That said, there is still some signal that can be extracted about how to moderate workload leading into competition in a way that sets players up for success by avoiding pre-event fatigue.

In Week 1 we are executing what we would call a very basic periodization approach to building up intensity over the course of a single week. The week’s first training day – Monday – is what we would call a Recovery day in the Skills That Scale Training Manual. What does that mean outside of a Driveline throwing program? Simply that we are going to reduce the player’s acute workload on this specific day of training by reducing their throwing volume and throwing intensity. This type of workout is exactly what a player coming off of a weekend’s worth of competition needs. We want them to throw as part of an active recovery activity protocol, but we want the intensity and volume of those throws to be low such that the player has a chance to recover from the Acute workload that was presumably created during the week or weekend previous.

The week’s second training day – Wednesday – acts as a bridge toward the third day of training on Friday. After the low volume low and intensity throwing on Monday we want to progressively increase workload on Wednesday such that the player is primed and ready for a higher level of workload on the third day of training on Friday. Not in a way that between Monday and Wednesday we would see a spike in their workload, but in a progressive and almost linear fashion if we were to look at a day by day progression to the workload we’ve created with each day’s worth of training.

Having progressively built up workload from our first two day’s worth of training, on Friday we are ready for the player to get back to a higher workload. This is an incredibly nuanced point, but an important one. If players are going to be throwing with high intent in competition it stands to reason that the first time that they’re going to experience the stress and the workload that competition will bring should not be in the competition itself. The game demands intent, and we want players prepared for the physiological effects of that demand.

So, on Friday we want to create a training environment for players that gets them up to the level of stress they’re going to experience in competition ahead of the game itself. This way we can prepare them for the workload that’s to come, and we also can do so in a way that we’re monitoring their outputs – velocity – and their mechanics along the way for any signs of fatigue. If we find any signs of fatigue along the way we can cut the workout short, and by doing so we also gain the knowledge of where the player started to show signs of fatigue in terms of their throwing volume, which is valuable information we want to have on our players going into competition.

Moving into the second week, we are generally running the same playbook. Monday is a low volume and low intensity training day to recover from the workload that was created by the high intensity workout the previous Friday. Wednesday is a moderate level of volume and throwing intensity to start building back up, but on the Friday leading into competition we are going to introduce another low volume and low intensity workload instead of doing anything resembling high intent prior to the onset of games. Again, we do not want to introduce fatigue before the event even starts. What we want instead is a player going into competition with a workload and readiness level that is designed to tolerate and accept both the volume and intensity of throwing a weekend’s worth of games is going to demand.

Moderating Throwing Workload In Competition

We can apply these same concepts around workload moderation when players are in competition. In a conventional tournament format, players are often asked to compete in a significant amount of games in a compressed amount of time. How do we do this safely? By avoiding as best we can the likely injurious configuration – players throwing and competing while fatigued.

If throwing in a fatigued state is the most critical thing we want players to avoid, then some of the standard behaviors when it comes to player pitching assignments during a tournament weekend are immediately called into question. Things like pitching twice in the same day, or closing out a Saturday game and starting on the mound on a Sunday, throw up immediate red flags because of how they affect a player’s workload. The inadequate amount of rest and recovery from the first to the second instance of pitching is going to increase fatigue. As fatigue goes up, so does injury risk. So we need to avoid these types of circumstances.

We should express similar amounts of caution when we mix pitching with position play – if those positions on the field are ones that combine high volumes of throwing with high intensity throwing. For example, having a player pitch and accrue a significant amount of throwing in workload in game one, then having that same player start at catcher in a 2nd game played on the same day, is a worrisome combination because of the high volume of throwing catchers have to perform, along with occasional high intent throws on runners trying to advance. The same could be said about players pitching in one game and then being the starting shortstop in the next, as your shortstop is generally doing nothing but making higher intent throws, as every throw they make is on a stopwatch with a runner trying to advance.

There are all sorts of edge cases here when it comes to this interplay between pitching and position play – so many that at present coming up with a hard and fast rule to define what is and isn’t safe is going to be challenging. Again, it must be said that at present if you want the most and best information on what a player’s throwing workloads are and how they are affected by all throws – on the mound, in the field, in the warm up, etc – then a tool like Driveline PULSE is mandatory. But even without this tool, if we simply understand that:

- All throwing has cost

- Fatigued players are more likely to be injured than non-fatigued players

then we put ourselves in a position to make choices that are more likely to keep players healthy than not. Sometimes that may mean simply making the least worst choice out of the available options. I’ll give you a specific example of what this means.

Practical Example – Making The Least Worst Choices

My son’s 11 year old Little League season was largely wiped out due to COVID. Fortunately we had started the Driveline Academy teams that year, so he was still able to train and develop while the larger leagues were shut down. When things got back to normal my son was determined to make the most out of his 12 year old season, and the Little League All Star Tournament that followed.

We dropped the first game, which meant that we had to win our 2nd game or we’d be in the “2 and a barbeque” configuration of having our All Star experience end prematurely. My son started that 2nd game and went 4 1/3rd 0H 3R 2ER 4BB and 9K’s on 89 pitches. With him at the pitch limit and our team needing to get 5 more outs to win the game – which would allow us to earn a 3rd game for the whole team – I made the decision to put him at Shortstop for the remainder. I knew that by doing so I was adding in some amount of calculated risk, in that there were going to be some amount of high intent throws he would have to make from that position that would add on to the workload that he had already accumulated pitching. But I also knew I could control the rest he would get in the next game, should there be one.

First, we had a day of rest between this game and when we would play next, should we win this current game. And in that next game he would not be pitching by rule, thanks to Little League’s mandatory MLB Pitch Smart compliance. Also I could position him in the field someplace where I would expect a lower volume or lower frequency of intense throwing if I observed (his velocity stayed or he reported any amount of fatigue or soreness prior to this 3rd All Star game we were trying to make it to. Fortunately, that was not the case. His velocity during the game he pitched did not fluctuate or dip, and he reported no soreness going into our 3rd game after the rest day.

Coming back to the game we needed to win, after my son came out of the game one of our relievers gave up a couple of runs to tie it in the top of the 5th. We then scratched a run across with 2 outs in the bottom of the 5th and closed it out in the top of the 6th, securing the win and our ability to play a 3rd game. In that 3rd game, with all of our more competitive pitchers exhausted by rule and unable to pitch, we just got beat plain and simple. And despite that not being the outcome we wanted, it’s ok.

I had 12 players on that All Star team. Today, only 5 of those 12 players are still playing baseball as far as I’m aware including my son, and honestly the number being that high is something I’m pretty happy about. For the time that I had that group of kids I did the best job that I could to moderate their workloads, keep them healthy and not let my conduct as their coach lead to an injury that would force them out of the game at some point now or in the future.

In the next installment of this series we’ll talk about how to optimize for development and setting players up for successfully making the transition from the small field to the big field. Stay tuned!

Comment section