A Closer Look at Sport Specialization

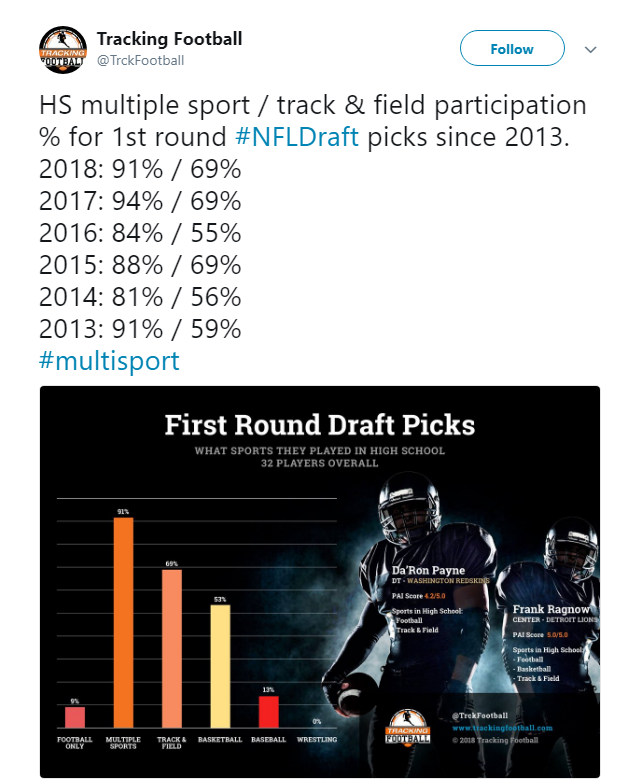

During the draft of every major sporting event, the topic of “sports specialization” is guaranteed to come up. You’ll probably end up seeing plenty of graphics like this:

Undoubtedly, there will be people who point out that many top-draft picks were multi-sport athletes, and because of that, you should be one too!

But should you? The actual answer, as usual, is it depends. There are a number of factors involved in becoming a high-level athlete in any sport, with whether or not to specialize being one of them.

Here we’ll break down some of the nuance around what athletes should do about specializing in baseball.

For the context of this discussion, “youth” athletes refers to athletes under the age of fourteen, or pre high-school. We’ll discuss and refer to other levels later because athletes’ ages and levels matter in the discussing whether or not to specialize. We can think of specialization as narrowing the focus of an athlete to focus on one sport.

First things first: Correlation ≠ Causation

We’ve touched on this topic before, but it helps to restate that many statements in favor of multi-sport athletes suggest that a multi-sport athlete is the main criterion for becoming a high draft pick. However, just because these two may seem to correlate, it does not mean that they are related in the way commonly assumed.

“Most pro athletes played multiple sports, therefore specialization is bad.” Reverses cause and effect

In fact, we should be able to acknowledge that better athletes are going to be in highest demand of every sport. At every age group, the athletes who are faster, stronger, throw harder, and rotate well are desired by coaches of all sports. This is especially true of youth athletes because the differences in skill levels among them, and those in early high school, can be drastic.

This means that the better athletes are going to get significantly more opportunities to play multiple sports than others—not to mention the fact that school size plays a role in the opportunities presented to athletes. Just by math alone, it is easier to play multiple sports with a school body of 500 kids compared to a school with 2,500 kids.

The effect of being a good athlete means you get pulled into more sports, it is not the cause

So most of these stats claiming that playing multiple sports leads to high draft picks multi-sport are not being used properly. We should realize that the amount of general athleticism needed to be drafted in any sport is usually incredibly high.

We should also note that certain sports pair much better with each other than others. We can draw many more similarities of ball movement and player position between soccer, basketball and even football than we can between one of them and baseball—not to mention how typical fall sports like soccer, football, and cross country pair very well with a sport like track in the winter and spring.

Now, this doesn’t mean that youth athletes should not play multiple sports, they should. It’s just not great way of getting to that point.

One reason youth athletes should take time off from one specific sport to play another is to give them a mental break from the game. Another reason is to keep amateur sports away from increasing professionalization. For example, we can see that youth sports are now an incredible $15-billion dollar industry.

“Sports Specialization” Is Often Used With Different Definitions

When specialization is talked about negatively, it is almost always framed in the a way that suggests these athletes are playing their sports competitively year-round. This often blurs the line between specialization and overspecialization.

Playing one sport year-round is often linked to injuries—mainly overuse injuries—which has been an issue for a long time as seen by the date of the New York Times article below:

When specialization is talked about positively, it often acknowledges that these athletes should take time off and train before competing again.

Now, there are some big differences between these two even though you rarely see them distinguished in an argument.

When trying to figure out where an athlete is on the spectrum, we should also ask, Who is driving the specialization? The athlete or parent? There can be a big difference between a parent who pushes for a youth athlete to play one sport and an athlete who decides he doesn’t like playing other sports.

Pressure to be great at a sport, and specialization in that sport, is often tied to the desire to play in college or play professionally.

Playing baseball specifically year-round is not going to be beneficial to an athlete’s development. Yes, athletes will improve by practicing the skills they need to perform in a game, but practice and training are different than playing.

Playing year-round is also closely tied to the politics and pressures of baseball, along with travel teams and the increase in year-round showcases. The perception is that every team and showcase presents one more opportunity to be “seen” by some scout to get that next chance at a scholarship or draft opportunity.

This is half true. Yes, athletes need to be seen to get a chance, but being seen isn’t going to help without skill and talent. Athletes get better by becoming stronger and training better, not playing. At Driveline, we’ve also had multiple athletes get college scholarships or pro contracts based on youtube videos alone, which supports the point that opportunities will present themselves—athletes just have to be really good first.

So Does Specialization Work? What Are the Risks?

It can work, but it’s no guarantee. The research suggests the injury risks are certainly higher, which is an important factor to consider.

While there are flaws in the specialization model, we cannot ignore the fact that many Caribbean and Latin American countries greatly prefer specialization and have developed some great baseball players. However, information on burnout rate and injuries is lacking, and we should also point out that the incentives are quite different as well.

We have to acknowledge that practicing or training more will get you better at a specific sport.

That being said, there is still a belief that being better at a younger age will give an athlete an advantage down the road in that same sport. The survey results from a recent study (Brooks et al., 2018) on sports specialization are eye opening:

- Only 45.8% believed specialization increased their chances of getting injured either “quite a bit” or “a great deal.”

- 91% believed that specialization increased their chances of getting better at their sport either “quite a bit” or “a great deal”

- 15.7% believed they were either “very” or “extremely” likely to receive a college scholarship based on athletic performance.

Contrast those numbers to a different survey study (Wilhelm, Choi & Deitch, 2017) of 102 current professional baseball players that found 48% specialized early, with the mean age of specialization being 8.91 years old. The study also found that those who specialized earlier reported more serious injuries while they were professionals—while 63.4% of the players surveyed believed that early sports specialization was not required to play professionally.

Another factor to consider is that it doesn’t matter how good an athlete is at a sport at the age of 10. It just doesn’t—playing on an fall all-star team, cool travel team, or having a “select invite” to a winter showcase at 10 may be fun, but there is no direct relationship between skill at that age and success in that sport later in life.

Another study (Erickson et al., 2017) found that between 2001 and 2009, 10% of the players in the Little League World Series ended up playing professional baseball—with 6 of the 638 players making the majors. And yet another study (Kearney & Hayes, 2018), looking at track athletes, found similar results: excelling as a youth athlete does not guarantee success later.

So do youths absolutely need to specialize before high school to become professional athletes? No.

What’s more, the downsides to early specialization are mental burnout and injury.

In a 10-year study, ASMI (Fleisig et al., 2011) found that pitchers who pitched more than 100 innings in a year were 3.5 times more likely to be injured. Playing year-round, on multiple teams, with increasingly smaller rosters are all variables that may lead youth pitchers to throwing more innings. This makes it all the more important how coaches run their travel teams.

Those same researchers also found that playing catcher appears to increase a pitcher’s risk of injury. This would suggest that because the gap in talent level in youth baseball is so large, better athletes are more likely to play more demanding positions and thus be at a higher injury risk.

One study (Yang et al., 2014) found no relationship between playing baseball exclusively and injury, but did find that pitching with arm pain and tiredness were associated with an increased pitching risk. There are two things we can take from this.

First, we can assume that playing year-round results in more chances for pitchers to throw with pain or tiredness. Second, like we mentioned above, not all specialization is the same; there are differences between competing year-round and just playing one sport.

So while there can be exceptions to the rule, it doesn’t seem that early specialization is the best way for athletes to reach their goals.

Of course this is still a simple look at the issue. There are underlying issue of teams and players having incredibly varied warm-ups and recovery protocols as well as having drastically different opinions on workload management and lifting. All of this factors into the risk of injuries.

Older Players of Certain Skill Sets Need to Consider Specializing to Meet Their Goals

At this point, we’d like to clarify that youth athletes should play multiple sports, because it makes them well-rounded. Different sports require different skills and types of communication to be successful, and it’s good for youths to have this variety. This should never be in question.

It should also be said that whether or not an athlete specializes in high school requires a different perspective from youth athletes. Once athletes hit high school, they should start to re-evaluate a few things to see if specializing in one sport makes sense to meet their goals:

An athlete’s decision to specialize in high school should be determined by his current skill level and what his goals are.

Age and skill are the important points in determining goals, these discussions should continue until a player enters high school and and then be more seriously considered as a player enters sophomore and junior years of high school.

Now, an incoming high-school junior who is an all-state baseball player and has been offered multiple college scholarships is probably fine continuing to play multiple sports.

However, the baseball player starting his junior year who has never been a full time starter but wants to play in college probably needs to make a different decision.

There are only so many top-level talents that we can hold up as examples until we realize that the majority of athletes have average skill sets but similar goals to the best players. Therefore, they need to make different decisions on how to reach those goals.

Pushing high-school athletes to be multi-sports athletes when they want to specialize ignores the fact that the more time athletes can spend training for their sports often means the better they can become. (Notice we said “training,” not “playing.”)

This shouldn’t be too controversial and is similar to the long-term athlete development plan that USA baseball recommends.

If you haven’t seen USA baseball’s long-term athlete development notes, they are worth reading, and this is a good start.

Decisions around specialization need to be considered in high school, but before high school athletes should try playing a variety of sports.

One More Note on High Schoolers

While participating in multiple sports is beneficial for youth athletes, we offer a quick word of caution for those playing multiple sports in high school.

One study looking at sport specialization (Jayanthi et al., 2015) found a strong relationship between specialization and spending more hours in organized sports and injury. Specifically, a high ratio of organized practice in relation to free play was a risk factor. Let’s use a baseball scenario to see how playing multiple sports can restrict free play or rest time.

With the increase of competitiveness in travel baseball, many teams try to lock in their rosters at the end of summer or fall while expecting to compete again the following summer. For teams, this does help them make sure that they have players, but it often comes with fall and winter practices.

This means a three-sport athlete could be playing football in the fall, with “optional” baseball practices on Sundays. This then leads to basketball in the winter and “optional” baseball practices on Sundays, followed by a competitive season in the spring.

Summer doesn’t get any easier. You could technically be in-season for baseball while going to football or basketball camps in the morning. These are potentially huge global workloads for high-school athletes, with very little rest.

Unfortunately, there isn’t an easy answer to these questions. Coaches are competitive as well and want certain players on their teams. This can lead to some awkward but necessary conversations with coaches who tell athletes that they have to go to certain practices or they won’t play.

So, parents and athletes may need to put their foot down and make certain decisions on which sports they are playing, or which practices they can make, earlier than they wish.

Help! My Son Only Wants to Play Baseball

How do you keep the specialized baseball player safe? Limit throwing and rotational load.

Being specialized doesn’t mean doing baseball-specific activities 6 days a week. The specialized baseball player needs to be lifting, taking care of mobility work, and everything else that makes a strong foundation. Ideally, these pieces are able to be implemented after a solid assessment.

What is not needed is to play more or try to get better by throwing more bullpens and taking more short flips.

Part of the reason that not specializing in baseball is good for youth athletes is that there is time away from rotating and throwing, which prevents overuse of patterns. It’s not that soccer, basketball, or football have skills that directly relate to being better at baseball; rather they improve general movement skills in youth athletes but they also give rest from throwing and rotating.

But if youth athletes do just want to play baseball, then they need to take adequate time away from throwing and rotating. They should still take significant time off—aim for at least four months off in a calendar year. Parents should also attempt to have two to three of those months off continuously. Remember, athletes need time away from both throwing and from rotating.

The way one-sport athletes can get better at moving, without throwing or rotating, is take the weight room seriously.

- While hitting, hitters experience 60-120% of their body weight in horizontal force and a peak vertical force of two to two-and-a-half times their body weight on their front leg (Fortenbaugh).

- Pitchers produce up to 150-175% of their body weight on their front leg when pitching (MacWilliams et al., 1998).

After you realize all these forces are already occurring when athletes are practicing, you can see why progressively training to get the body stronger and better at accepting and creating force is a huge benefit.

Lifting for youth athletes doesn’t need to be complicated; it needs to be consistent.

To create and maintain consistency, covering the basic movement patterns and focusing in on technique are the key.

Squat, hinge, push, pull, move laterally, do some fun work. It’s going to involve education and practice.

If an athlete insists on doing baseball work, it should be unstructured. Taking grounders or fly balls can be fine; just don’t have them throwing.

Lastly, these extra baseball activities need to be driven by the athlete, not by the parent or coach.

Planning Is the Key

Here is the biggest piece of actionable advice we can give: parents and athletes need to take time to plan and evaluate what they are doing and when.

Youth and high school athletes and their parents should ask themselves:

- What are your goals?

- When was the last time you took time off?

- When do you plan to?

Points two and three can be asked for both one sport and multiple.

It best to think of an athlete’s schedule by looking six months back and planning six to twelve months ahead.

This gives you the best chance to get a wide look at things and start planning when athletes are competing, what sports they want to play, when they can take time off to train, and when they have time to rest.

The most important question is not about whether or not to be a multi-sport athlete. It’s what athletes want their careers to be and how far they are willing to go to meet their goals.

There is nothing wrong with playing sports for fun, and there is nothing wrong with setting a high goal in one sport and working towards it. But everyone needs to have a plan.

Athletes should come up with goals and get help from their parents to schedule how they can reach them. Then re-evaluate where they are and then decide on the best path moving forward.

This can be every year for a youth athlete or before a season to see if what sports they are interested in playing. In high school, decisions can be re-evaluated every season because factors in their control, such as skill level, and outside their control, school size and coaches, are going to impact their planning.

Then can then re-evaluate every season and see how, and if, their goals have changed and what they can do to train for them.

Wrap Up: Key Points

There is a lot of nuance in the discussion of sports specialization. We covered a lot of topics, so let’s recap the main points:

- Correlation ≠ causation: Better athletes get more opportunities to play more sports; playing more sports doesn’t always make them better at one.

- Overuse injuries in youth sports have been around for a long time; there isn’t a good reason for youth athletes to play one sport competitively year-round.

- Specialization can work, but it comes with a higher injury risk, especially if specializing as a youth athlete (pre high school).

- Athletes in high school need to evaluate their current skill sets and goals to see if they should specialize.

- Multi-sports athletes need to manage their workloads and make sure they are getting time off and not overlapping schedules.

- If youth athletes only want to play baseball, they need adequate time off from rotating and throwing.

- Getting stronger and learning how to lift is vital for all athletes.

- Athletes and parents need to sit down and plan their time, what sports they want to play, and when they are going to take time off.

Works Cited:

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jeremy -

Great write up & break down of sport specific training.

Jeff Harris -

Right on the money about issues trying to manage a kid who plays multiple sports and a coach that wants them at the indoor doing baseball stuff 9-10 months a year and possibly playing spring, summer and fall seasons. When there are kids that want to play the same position and only play Baseball and your kid plays 3 sports, it gets tough to continue down that path when they could/will end up with less playing time because of that.