Return to Throwing Program for Pitchers

The traditional model for phases of rehab that occur after Tommy John surgery look something like this:

- The player has surgery and their arm is placed in a locked brace that limits flexion/extension at the elbow

- They are then given a stretching and mobility program. This is in order to gain full flexion and full extension before doing strengthening exercises. This process can vary depending on the surgeon and physical therapist but is largely similar across the board.

- The patient begins a “throwing” program

This blog will focus on improvements that can be made in a return to throwing program.

ThiThis blog was updated on 6/3/2022 and was written by Dean Jackson and Kyle Lindley, edited by Michael O’Connell

Problems with Interval Throwing Program for Tommy John Rehab

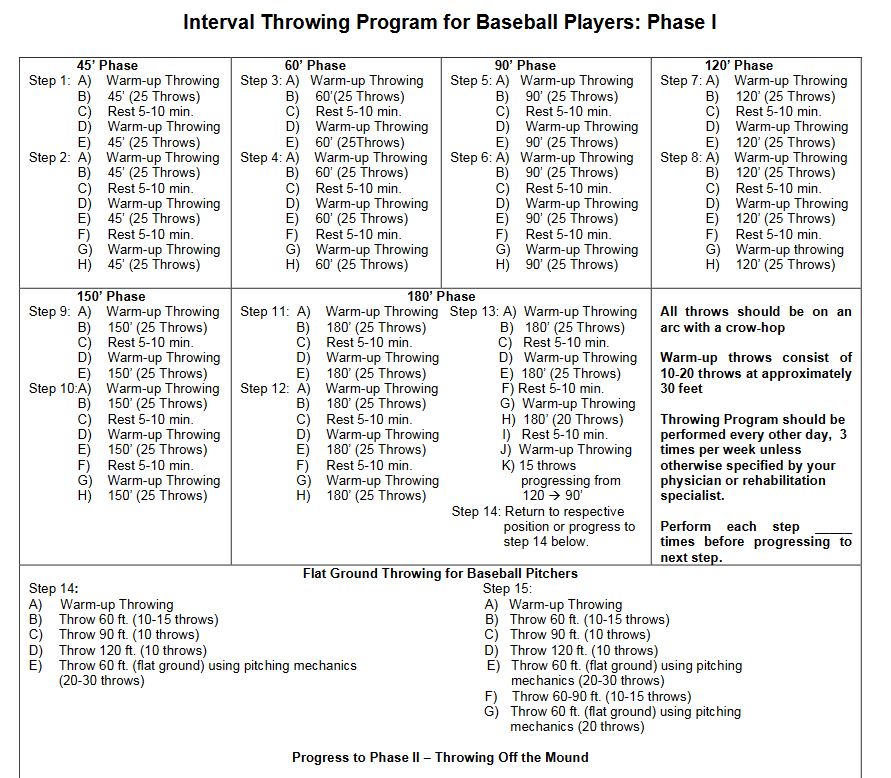

Below is an example of what an Interval Throwing Program may look like.

It’s our opinion at Driveline Baseball that this type of program has three major flaws:

- Misapplication of volume and intensity

- It lacks monitoring of any kind outside of distance

- RPE has its flaws in being a measure of intensity

- No straightforward adjustments for missed days/soreness etc

Let’s break them down:

Poor Application of Throwing Volume and Throwing Intensity

Your first day throwing on this program involves two sets of “warm-up throws” and 50 total throws from 45 feet. If you split the difference on the warm-up throws and call it 15 throws each (10-20 per the document), then you are making 80 total throws on your first post-surgery throwing day!

The most common side effect of these types of programs involves soreness and setbacks due to the inability to overcome the volume of the program. This can create a vicious cycle of starting, stopping, and restarting a throwing program.

Our article detailing “pulldown” throws goes into a bit of detail, but players need to be tested at game-like intensities before they return to competition. We need to make sure that they are occurring at the appropriate time

Distance Monitoring isn’t Enough for Return to Throwing Programs

Secondly, there is no monitoring outside of distance. Pitchers going out to 180 feet on this program do so at varying angles, velocities, and intent. Throwing at 40 mph or 60 mph at 60 feet should not be equal.

This program cannot be equally effective for the MLB pitcher who sits 95 MPH and the 17-year-old who sits 83 MPH. Other than different starting points, there are drastically different resources available to one over another.

Do Players Throw at the Intensity They Think?

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) also has its flaws as a measure of intensity.

Previous research has shown that the percentage of effort that a pitcher is trying to throw at does not correlate strongly with how hard the pitcher is throwing compared to their velocity peak (Slenker, Limpisvasti, et al. – Biomechanical comparison of the interval throwing program and baseball pitching: upper extremity loads in training and rehabilitation AJSM May 2014).

At 60% of perceived effort, pitchers were generating forces of 76% and ball speeds approaching 84% of maximum intensity.

Pitchers are really bad at estimating how much effort they are expending and consistently underestimate it. This should have profound implications for rehabilitation programs.

How Do you Make Adjustments?

Programs are often written in a way that doesn’t account for the rest of a player’s life.

Some baseball players returning from surgery have a nice, smooth recovery process. Others do not. Some players’ bodies won’t let them progress for a few weeks. Other athletes feel incredible, and they feel ahead of schedule. It’s a rollercoaster to try and help a player along with Physical Therapists and surgeons.

They are difficult to adjust in all areas because everyone recovers and adapts at different rates.

Everyone recovers and adapts at different rates.

Because of this, there will often be some sort of setback due to throwing volume and intensity. After all, everyone will respond differently to a program. But we need to remember that other factors outside of the throwing program can also cause setbacks. Lack of sleep, varying nutrition, school load, or travel are a few reasons that can also cause setbacks.

Principles of Return to Throwing Program

The fact of the matter is tools exist today that can raise the standards of Tommy John rehab. We want a standardized approach but an individualized method.

The solution is to use technology to better track progress and make programs individualized. This means utilizing

- A Pulse sensor to monitor Arm Speed and the number of throws a player is making

- A radar gun to measure how hard a pitcher throws

Combined with subjective measures, these objective measures give us the best chance for the next revolution of rehab programs.

Phases of a Tommy John Return to Throwing Program

Using Pulse and a radar gun, we can monitor the following variables:

- Amount of Throwing

- Intensity of Throwing

- Frequency of Throwing

- Progression of Throwing Volume

- Progression of Throwing Intensity

- Expected “Stress” Based Upon Pre-Injury Information

You can read more about the metrics on Pulse here.

We can use those to better supplement subjective measures by asking the athlete questions such as:

- How did your arm feel today?

- Was the prescribed intensity too high, too low, or just right?

- Was the prescribed volume too high, too low, or just right?

We can combine these to create the four main phases of our return to throwing program:

- Build Volume at Low Intensity (4 weeks)

- Begin Undulating and Increasing Intensity (6 weeks)

- Continue Undulating and Increasing Intensity with Longer Recovery (6 weeks)

- Step Back Intensity, Increase Frequency, Gradually Increase Intensity (12+ weeks)

We can layer on more extensive monitoring with Pulse and Radar Gun inside these phases.

Using Arm Speed as a Guide

Arm Speed will be used as our primary monitoring tool until ~700 RPM Arm Speed. Reaching ~700 Arm Speed typically occurs after several weeks of throwing.

Once ~700 RPM arm speed is reached, we would switch to a combination of arm speed and throwing velocity. Arm speed and velocity would be used to continue progressing intensity through the remainder of the rehab. We choose ~700 RPM Arm Speed because that is approximately where Pulse Arm Speed starts to deviate from throwing velocity.

We would progress intensity using object data (arm speed and throwing velocity) and subjective data from that point on. Focusing on how he felt he was recovering, how his mechanics looked like his, and how his body responded well to the increased intensity.

The example below is from a return to throwing program with athlete Ryan Cloude. This example represents a sample of what can be done with a data-driven return to throwing program. The advice dispensed in this article would certainly not work for everyone for the reasons stated above. We know how weighted balls affect the torque on the arm and workload, the example program below only used baseballs.

Data-Driven Return to Throwing Program

Ryan Cloude is a 21-year-old collegiate pitcher. He has an interesting training history, having increased his pitching velocity from 83mph as a college freshman to topping at 95mph as a junior. In the middle of his junior season, he tore his UCL and required UCL reconstruction.

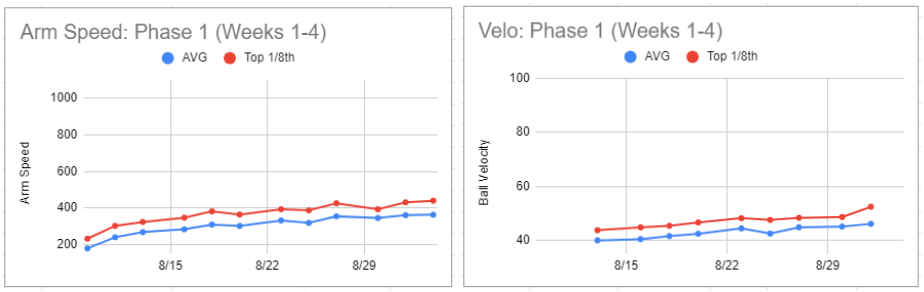

Phase 1: Build Volume at Low Intensity

The goal of this phase was to build a throwing volume base at a low intensity. We start all our athletes off with a low threshold to set them up for increased intensity later.

Ryan threw 3x per week during this 4-week phase. We monitored Arm Speed with Pulse, gradually increasing from a one-session average of ~200 RPM and top 1/8th ~250 RPM to a one-session average of ~350 RPM and top 1/8th ~450 RPM.

Total throws per session increased from 25 to 90 from the beginning to the last day of the phase.

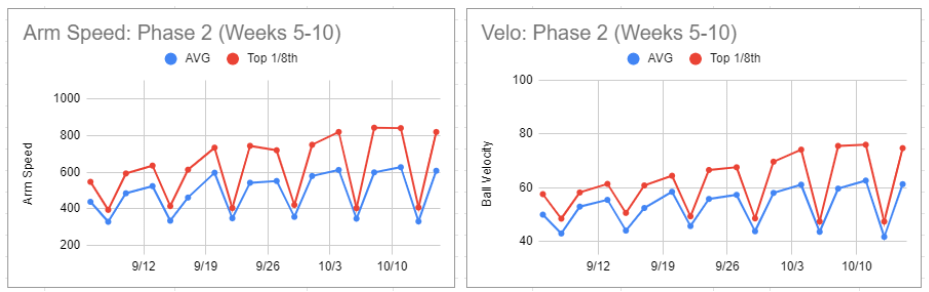

Phase 2: Begin Alternating Intensity

We built this phase of the throwing volume base established in Phase 1 by increasing the throwing intensity on Monday and Friday each week.

Once Ryan hit the ~700 RPM arm speed mark, we switched measuring intensity from Arm Speed to throwing velocity.

Over six weeks, Ryan’s Arm Speed increased from a one-session average of ~350 RPM and top 1/8th ~450 RPM to a one-session average of ~600 RPM and top 1/8th ~850 RPM. His velocity increased from a one-session average of 49.9 mph and top 1/8th 57.6 mph to a one-session average of 62.6 mph and top 1/8th 76.0 mph.

Instead of throw counts, Ryan was given options between 60-90 throws on the higher intensity days. At the same time, lower intensity days progressed gradually from 90 to 120 throws. He did the max number of throws most days, except for three days where the daily notes had some variation of “another crazy conditioning at 6 am this morning, body felt dead. Stopped at 60 throws”—no arm-related reasons for throwing less than the max throws.

One week, the same intensity was repeated (instead of progressing it) because Ryan was exhausted from team conditioning and didn’t want to push it.

Return to throwing templates lack guidelines on how to make adjustments to the program. At times the adjustment doesn’t need to be because something went wrong with the throwing program. But other parts of a player’s life are still ongoing when rehabbing a throwing injury. Tracking these programs leaves a player and a coach in a much better place to make an appropriate adjustment.

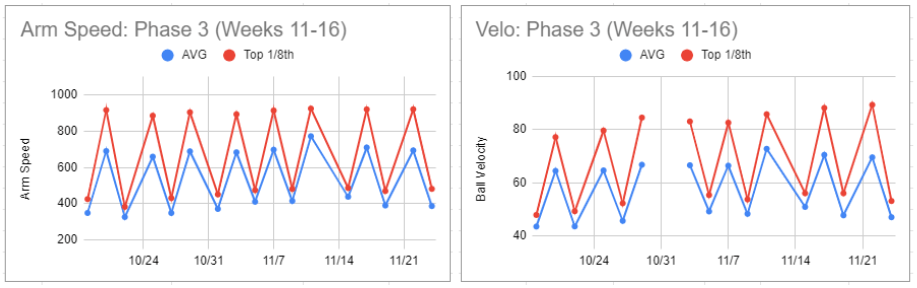

Phase 3: Continue Alternating Intensity with Longer Recovery

The only difference between the schedule of this phase and the last is that instead of the weeks going HLH, HLH (higher intensity, low, higher, and repeat), they went HLH, LHL (higher intensity, low, repeat). This shifted Ryan from 4 higher intensity throwing days every two weeks to 3 high-intensity throwing days every two weeks.

There were two new additions in phase three. First, bullpens at lower intensity began in this phase. Second, we started to focus more on moving efficiently. We measure movement efficiency by throwing the prescribed velocity with the lowest possible arm speed.

Over six weeks, Ryan’s Arm Speed increased from a one-session average of ~600 and top 1/8th of ~850 to a one-session average of ~700 and top 1/8th of ~ 925. His velocity increased from a one-session average of 62.6 mph and top 1/8th of 76.0 mph to a one-session average of 69.6 mph and top 1/8th of 89.4 mph.

His volume options remained 60-90 on higher intensity days and 90-120 on lower intensity days. Ryan decided not to throw the max amount of throws on a given day: total body soreness from training with his team and getting kicked out of the gym as it was closing. No arm-related reasons for throwing less than the max throws.

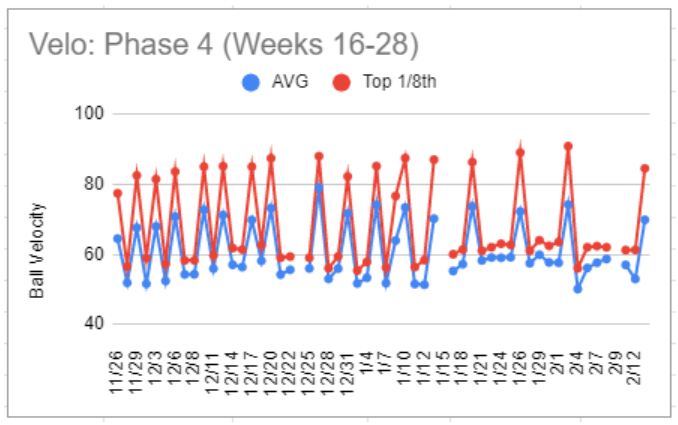

Phase 4: Step Back Intensity, Increase Frequency, Gradually Increase Intensity

Bullpen throwing velocity was dropped back to the high 70s, with two pens being thrown each week, and lower intensity days were added over a couple of weeks until Ryan was throwing five days a week.

Throwing velocity on main bullpen days gradually increased from a one-session average of 64.5 mph and top 1/8th of 77.4 mph to a one-session average of 74.2 and top 1/8th 90.9 mph.

We had phases that we wanted to progress through and a good idea how roughly how much we should progress over a certain period, but ultimately we let Ryan’s body decide if it was ready to progress or not.

If the prescribed intensity for a session wasn’t comfortable, we would not progress intensity in the next session (regardless of what the program template said). We would repeat the intensity (or reduce it) until it was comfortable. The main idea in the intensity prescribing process was “letting the door be opened” when Ryan’s body was ready and not trying to “kick the door down” and force a more intense stimulus on his arm before it was ready.

Handling Bullpens and Offspeed Pitches

Other pitch types were added first to recovery days during this phase. Simply by throwing offspeed in flat ground or catch play/long toss work. Intensity and volume were gradually increased until Ryan was throwing at maximum intensity on the mound.

Volume options for total throws on each bullpen day gradually increased from 60-90 to 90-110, while volume options for lower intensity days stayed 90-120. Once Ryan’s velocity got back into the high 80’s a few bullpens turned into recovery days because he didn’t feel fully recovered.

The first live session versus hitters happened roughly 10.5 months post-op and went well enough that Ryan decided he was ready to face hitters in a game that counted for his team. The first outing versus hitters in a real game happened just before the 11-month post-op mark and resulted in 1IP 0H 0BB 3K.

Return to Throwing Program Reflection

After completing his return to play, Ryan reflected on the process as a whole:

“Having objective data to show my progress was massive for my mental state. On days where I wasn’t able to hit my goal or days where I felt I was so far away from being healthy, I’d be able to look back and see how much harder I was throwing and how much more arm speed I was able to handle.”

It’s widespread to hear athletes talk about the mental toll injuries took on them and how grueling the whole experience is. I believe collecting data to give athletes a good idea of where they are now, where they have been, and where they need to go can significantly improve how comfortable their experience with rehab ends up being.

Ryan also said:

“(I) loved having a progression based on how I was recovering and not a cookie-cutter program that’s the same for everyone.”

- Improved monitoring of arm/body mechanics and workload (kinematics, kinetics, chronic/acute stressors)

- Better communication between skill-specific coaches (baseball) and medical professionals (Physical Therapists, Orthopedic Surgeons, Manual Therapists)

We’re attacking it via our integrated staff training methods, technology, and Driveline TRAQ – and results have never been better, both on the performance AND rehab sides.

Not sure which training program is right for you? Schedule a time for a Driveline trainer to call you.

Comment section